03/21/2019

Consumer

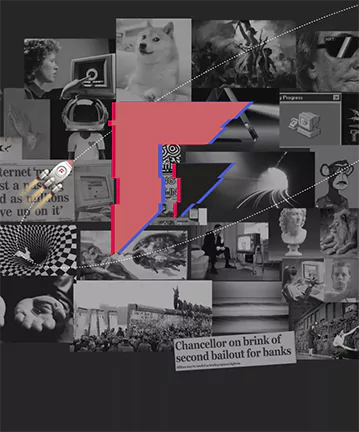

Risky business.

With the “low hanging fruit” picked, online marketplaces must absorb and mitigate risk on behalf of customers.

In all likelihood, the first business ever created was a marketplace.

Open air, public bazaars date back to 3,000 BCE in the Middle East and have formed the center of civic life for millennia. Such a simple idea — to aggregate haggling buyers and sellers in a public forum — is perhaps as old as trade itself.

The first online marketplaces were the equivalent of public bazaars. These platforms provided little value above and beyond the essential matching of buyers and sellers. eBay was the poster child. At the time of its 1998 IPO, it collected ~6% of GMV by charging sellers a variable success fee, as well as small fee per listing. In its S-1 filing, eBay described this super efficient business model:

The Company’s business model is significantly different from many existing online auction and other electronic commerce businesses. Because individual sellers and not the Company sell the items listed, the Company has no product cost of goods sold, no procurement, carrying or shipping costs and no inventory risk. The Company’s rate of expense growth is primarily driven by increases in headcount and expenditures on advertising and promotion.

The simplicity of eBay’s service ultimately made it wildly profitable, with gross margins of ~90% and positive net income at IPO. This “low hanging fruit” era of the internet supported a fast growing marketplace that took on little risk outside of its core matchmaking function.

More than two decades later, another marketplace, Lyft, filed to go public. Its S-1 tells a much different story.

Compared to eBay, Lyft does a lot more heavy (ahem) lifting to create liquidity. Its contribution margin today is 46%, much lower than the comparable 90% gross margins at eBay. The difference comes from the additional technology, payments, and insurance costs associated with managing a real time transportation marketplace. However, Lyft’s take rate of 29% is much greater than eBay’s original 6%. Simply put: Lyft is getting paid to do all that extra work. In fact, combining take rate and margin, Lyft produces $13 margin dollars for every $100 of bookings vs. only $6 for eBay at the time of its IPO. The latter is closer to $8 today. Lyft extracts almost twice the value per transaction compared to eBay.

If eBay and Lyft are indicative of a larger trend, the story they tell is that, as marketplaces have become much more “managed” in the last 20 years, they’ve also become more profitable. In the next 20 years, marketplaces must continue not only to provide more functionality for customers, but also take on more risk their behalf. Risk signals friction in a transaction. By owning transactional data over long periods of time, marketplaces can do a better job than participants on their own in underwriting and, therefore, mitigating that risk.

Faire, for example, realized that retailers were hesitant to try new products in their stores, for fear those products would not sell. This insight inspired Faire’s core business model, in which it offers free returns and net 60 payment terms to retailers on new brand purchases. Faire takes the risk and centralizes it. In doing so, it both unlocks liquidity and builds a data asset that scales in value with the size of its platform.

Lambda School has also taken the approach of centralizing risk to reduce friction. Students seeking to learn a skill are skeptical of new programs and often doubt their own long-term commitment to the hard work of learning a tradecraft. Lambda removed all risk for students by creating an “Income Sharing Agreement,” wherein revenue is paid out of the student’s income post-graduation. Each admission decision at Lambda is effectively “underwriting” that student. The more students it admits, the better it should get at deciding who will benefit most from the program.

Care.com provides a tragic counter example. Its recent actions showed how absolving yourself from risk in a marketplace can cause liability in certain categories, like childcare. Care.com disclaims responsibility to certify if childcare providers are licensed and listed with accurate data. Comparing itself to job search sites like Indeed, Care.com does not interview users, nor does it conduct background checks. Caveat emptor is its approach. The big difference between Care.com and Indeed is that users trust Care.com to, I dunno, *care* about how children are treated when matched with a provider. Care.com would need to take on more risk (and more cost) in order to validate users, but then again it could also avoid horrible outcomes. I expect a startup disruptor to adopt a risk-taking approach to the childcare market, guaranteeing a safer alternative to parents and aligning incentives in a more thoughtful manner.

Marketplaces will continue to be compelling online businesses, but will increasingly be required to “do more” on behalf of users. Taking more risk will create more value, which means that the marketplaces built in the next decade can be even more valuable than those built in the last.

Authors