By James Ledbetter

For decades beginning in the 1960s, there was a running gag in the Peter Sellers’ Pink Panther movie series. Sellers’ bumbling character Inspector Clouseau employed a man who was assigned to attack Clouseau when he least expected it, just to keep him on his toes.

That character’s name was Cato—the namesake for the Israeli-based cybersecurity and networking company, Cato Networks, recognized on this year’s Fortune Cyber 60 list, presented by Lightspeed.

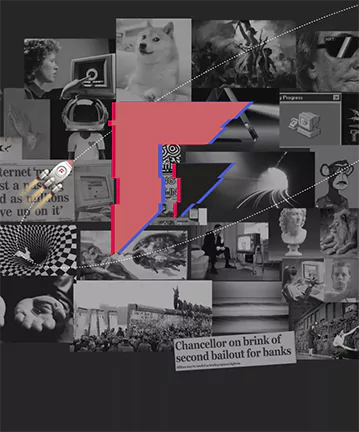

Shlomo Kramer, Cato’s CEO, co-founded the company in 2015. But Cato is far from Kramer’s first stab at cybersecurity. His experience dates back to the earliest days of the public internet, when hacking was little understood but could immediately shut down a company’s computer system out of nowhere, a bit like Clouseau’s Cato.

Kramer, 57, recalls that the idea for his first company grew out of his youthful time serving in the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). The IDF regularly recruits Israel’s best math and science students as part of their compulsory military service, and placed Kramer in its elite 8200 unit, which focused on what was not yet widely called cybersecurity.

Kramer and his IDF colleague Gil Shwed took what they’d learned from their military service and founded Check Point, inventor of the commercial firewall and one of the earliest cybersecurity firms of the dot-com era. “We sat down and wrote a completely new type of product that fits on a single floppy disk, five minutes to install, and boom, you’re protected when you’re connected to the Internet,” Kramer recalls. “Today, it sounds trivial. But back then it was completely groundbreaking.”

Kramer looks at that early experience as a kind of 1.0 version of cybersecurity, that made him something of a celebrity within the cybersecurity world. Since then, he has founded another successful cybersecurity firm, Imperva, and now Cato Networks, a cybersecurity firm that is based in the cloud, where a huge portion of business takes place these days.

A recent Gartner report projects that by 2025, 80% of enterprises will have adopted a strategy to unify web, cloud services and private application access using a system like Cato’s, up from 20% in 2021.

“At the heart of what we do is complete obstruction of location,” says Kramer. And yet, for any Israeli company these days, location remains all too relevant. During a video interview for this article, one of the subjects stood up and started to leave the room because he thought he heard warning sirens. It was a false alarm, but a reminder that security threats are hardly a thing of the past.

The world of connected devices has expanded exponentially since Kramer and his colleagues first started thinking about cybersecurity. Even beyond the obvious increase in Internet-connected computers and smartphones, nearly every aspect of our lives is now hooked up to cyberspace: our cars, our refrigerators, our keychains. The size of the global cybersecurity market is currently about $175 billion and is projected to grow to $266 billion by 2027. “People work everywhere,” Kramer notes. “Applications are everywhere.”

Kramer saw early on that this was the trajectory for cybersecurity. As life became more digitized in the 21st century, the need for cybersecurity grew explosively, but in a clunky and fragmented way. The cybersecurity industry became dominated by global telecom incumbents, each peddling its own hardware-heavy and expensive solutions. For decades, networked computers in a given company or workplace were monitored by legacy hardware security approaches. Simply layering security on top of antiquated systems not only increased complexity but was often very costly.

“It became extremely hard to build a security solution that can meet the demands of digital business,” Kramer explains. “The agility, visibility, movement, and velocity — all of these things are extremely hard to do when you’re stuck in the previous generation with just a ton of appliances and widgets and whatnot.”

Kramer recalls attending a trade show in Paris in 2015 and viewing the presentations offered by the likes of AT&T and BT. After a couple of days, he called his partner Gur Shatz and said: “This is never going to happen.” The pair realized that a cloud-based cybersecurity solution was needed, and that’s how Cato was launched.

It’s not just that converging many network security tools meant fewer tools to learn and operate so security became simpler to run. Alone that would be revolutionary. But Kramer also understood that ironically with many security products came increased risk. Security teams understood less about their network as key data points were siloed behind the many different tools. Cracks in the infrastructure were left open between the tools, allowing threats to sneak through. With more tools, there were also more updates to apply.

As cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier once noted, a simpler network is a more secure network, and Kramer and Shatz understood that very well. So they converged those tools into the cloud where all sites, users, and cloud resources worldwide could be protected by the same global network security platform.

Cato’s signature innovation was recognized in a landmark 2019 Gartner report. Gartner coined the term “secure access service edge” (SASE), which Cato has since adopted as a kind of branding.

The timing was fortuitous. The outbreak of COVID in 2020 led to a massive shift among enterprises to hybrid work. The work-at-home phenomenon sent enterprises scrambling to evaluate, select, and deploy the necessary infrastructure to connect remote workers. For many, the process took weeks even months. But with Cato’s unique cloud-native architecture, enterprise customers were able to make the shift to hybrid work in hours.

Hybrid work was one powerful use case of Cato, but not the only one. Cloud migration

became much easier. Instead of purchasing premium cloud connectivity to connect cloud resources, Cato customers could easily connect cloud instances to the Cato SASE Cloud. Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) took a fraction of the time as enterprises found they could quickly connect and secure the new locations and remote workers with Cato.

Kramer likes to say Cato “brings Fortune 500 security to the masses” but no one should think that Cato is only being adopted by small companies or even specific industries. A look at Cato’s customer portfolio shows a diverse range of industries and company sizes.

For example, Carlsberg Group, the third-largest brewer in the world, selected Cato to transform its global infrastructure. “Cato is so much simpler to deploy and use than competing solutions,” says Tal Arad, Vice President of Global Security & Technology at Carlsberg. “We started referring to them as the Apple of networking.” When complete, the deployment will span 200+ locations and 25,000 remote users worldwide. Instead of the existing security appliances dotting their sites and locations, Carlsberg will rely on the full complement of Cato’s cloud-native security capabilities to secure and protect not only locations but also remote users worldwide.

“The savings we get with Cato and HoloLens are almost impossible to count,” says O-I Glass CIO CIO Rodney Masney at O-I Glass, one of the world’s largest glass bottle and jar manufacturers for leading food and beverage brands.

The Cato infrastructure was so much more efficient and effective than legacy approaches that O-I Glass engineers in the US could don Microsoft HoloLens augmented reality headset to show personnel in Asia how to troubleshoot factory problems. The company adopted Cato worldwide, improving security and user experience for its 24,000 work-at-home employees and 200 locations..

One way to think of SASE is that it combines the networking of computers with the idea of securing them. “We’re the AWS of network security,” Kramer says, referring to the Amazon Web Services, which provides compute and storage cloud services to more than a million businesses worldwide.

Still, even the most innovative businesses require funding and other assistance. Yoni Cheifetz has been an Israeli-based Lightspeed partner since 2006, and a tech entrepreneur whose path crossed with Kramer’s a few times over the decades. He recalls conducting a due diligence inspection with technical experts before Lightspeed invested in Cato in 2019. While he was impressed, he was also concerned that Cato was trying to take on numerous tasks at once. “I would probably not invest in something like this if it wasn’t Shlomo running it,” he says bluntly.

The Israel connection is crucial. Cheifetz and Kramer have known each other for years; Kramer is also an investor in addition to being an entrepreneur, and there have been board overlaps between Cato and Lightspeed for some time. “We are an Israeli company,” Kramer says. “All of the headquarters are in Israel. And we’re very proud of it. And that was a design goal for me.” Obviously, the country’s conflict puts tremendous strain on the company and its employees, but it’s also a fitting reminder of Kramer’s IDF roots.

While Cato has grown tremendously in its first few years of operating, the business nonetheless has its challenges. It’s well-known within the cybersecurity industry that finding talented employees is difficult. Some surveys have shown more than three million unfilled jobs in cybersecurity worldwide. “There’s simply not enough people out there,” Kramer laments.

Another complexity comes from artificial intelligence, which can multiply both the volume and complexity of security threats that any company or institution might face. Kramer approaches the issue philosophically. “The problem is not technology,” he says. “The problem is human nature. Once they invented the toothpick, the first usage was as a weapon.” The only solution, he argues, is to fight AI fire with AI fire.

One particular area where Cato has deployed AI is in halting phishing and ransomware attacks. Traditionally, cybersecurity firms have used lists of disreputable domains in order to identify potentially malicious emails. The problem is that the attackers can quickly generate new domain names that don’t appear on the lists. Cato now uses AI and deep learning to identify malicious domains in real time. In testing, its approach has identified six times more malicious domains than the reputation lists alone. “We are the first company to put AI into protection, not only detection,” Kramer says.

As advanced as the business may get, it’s always on the lookout for an attack on Clouseau.

Learn more about the Fortune Cyber 60 and Lightspeed CISO Survey.