During the pandemic I have been making feeble attempts at getting back to playing the piano again. Took a few online classes to warm up and yesterday, during a lesson, my teacher asked me about past exposure to music (beyond listening), and from there the conversation shifted to why I seem to love playing Chopin so much. Well, how does one articulate that? I didn’t like how imprecise my answers were, so I decided it was time I brush up on my music theory and put this down on paper.

Before I say anything about Chopin, I have to acknowledge that it is damn near impossible for a non-polish pianist (amateur, or otherwise) to play Chopin as was intended – just impossible. Chopin’s music is as much about the body as it is about the soul. There is not just a pulse, but a living pulse in his compositions. Without being in sync with this polish pulse, a lot of his Ballades, Mazurkas, and Waltzes – pieces that are especially linked to old polish poetry, nationalist movements, or just the polish way of life – are lost in mere metronomic detail.

Bach, who used the contrapuntal — a way of writing / playing music such that multiple harmonically inter-dependent yet independent motifs in rhythm and melodic contour often live in the same composition — was a major influence on Chopin. Chopin, however, moved away from Bach’s controlled, logical style. Where Bach was emotional yet non-romantic, Chopin was more combustible, and intellectual, and his logic was not as unrelenting. His compositions weren’t as cross-referential either – notes that began a piece often never showed up again, and when they did, they did so in a different chord. This may have been heresy in those days. Still, the whole idea was very well thought through. Let me give a quick example:

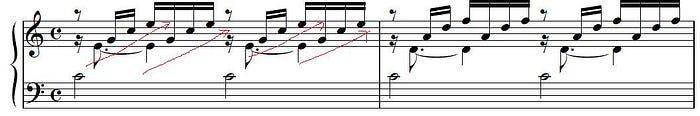

A very simple Bach prelude, BWV 846 Prelude 1 in C

So Bach bases his piece on simple chord progressions, which is exactly the idea Chopin took to heart. Additionally, in Chopin’s compositions, these structures – the Chorals – were interspersed with complex harmonics. A Bach prelude can be played with your fingers relatively static and hovering on the piano, but no such luck with Chopin.

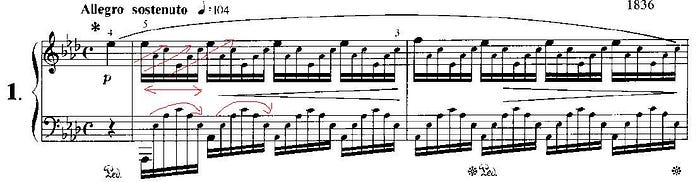

Take the following skeletal chord progression for a Chopin Etude:

Note carefully as you listen to the fully fleshed Etude (Etude op.25 no.1, “Aeolian Harp”)…

…how these few chords are mingled with layered arpeggios (roughly speaking, playing the chord in ascending or descending order) – the little-finger of your right hand pretty much carries the tune here, and the little-finger on your left is no less important in providing clearly audible ends to each arpeggio. Sounds simple, but incredibly complex to play, especially toward the end where the gaps between the final and the penultimate note within each arpeggio increases significantly, seriously compromising the legato — the smooth flow of tone without breaks between notes of the piece. That’s Chopin.

Now, let’s take one of my favorite pieces by Chopin, the Mazurka in A minor Op.17 No.4, which is the perfect piece to demonstrate Chopin’s greatness. Let’s start with the first 20 measures from this Mazurka.

Note how the piece begins: almost floating, ethereal. We can’t tell what the key is, nor the rhythm. This is quite unlike the baroque masters who usually disclosed a lot about the piece in the first few measures. An A-minor piece such as this usually would have traditionally begun with the A-minor chord, but Chopin chooses to start with dissonance instead – very bold choice, especially when all the other romantic era composers were towing the line:

However, there is a lot more to the beginning. The three notes that start the piece…

…get repeated thus: [FBA, FCA, FDA], [FBA, FCA, FDA]. The third time, we have FBA, FCA, and then a decorative DED, giving the feel of a dance – a Mazurka indeed – before we move to notes FCA. Now begins the fun part. Note how the F?A chord carries the three notes B, C, D, that eventually become the Mazurka tune (see red notes above), and the ending of the introduction (DE?), becomes the next fragment of the Mazurka tune:

So even in that suspended, dream-like sequence, there is a well planned structure that hides the guts and the sewers of this monument. A lot of harmonic control just to allow for such an improvised salon-like feel. This is a completely new kind of relationship between the introduction and the main body of a piece, and downright impossible to find in any of the baroque compositions.

As the melody reaches the D where it desperately wants to resolve to a major chord, Chopin takes us to the heart-rending E …

…and then voila: dissonant again;

…all hopes dashed – almost Debussy-like! After two dissonant notes, he refuses to copy it a third time like any other composer would, and moves to a short-long, jerky, heart-stopping rhythm at CG#:

From there, we move on a beautiful set of somewhat improvised notes

and another quick jab before we reach an exceptional sequence marked delicatissimo:

…the heart of this piece – what Chopin had been leading us to all this while. All this while, note how the left hand is progressing lower one chord at a time…

…slowly like a drunk baroque master! Sounds improvised, but carefully arranged by the most masterful and deceptive composer of all time. Try your bel canto on this, Rossini/Bellini/Donizetti!

I totally believe that if not for Chopin, we’d still be listening to uninspired contrapuntal Bach for the past 400 years, or at least till Satie came to the fore. And finally, here is the full Mazurka played by Artur Rubinstein (and yes, he’s Polish).

And another one of my all time Chopin favorites:

Authors