For a business that was established in the 19th century, the last five years have been extraordinarily tough.

H.L Stores stands on Ibrahim Saheb Street, a by-lane of Commercial Street, a popular shopping hub in central Bengaluru. The red and white signboard atop the storefront announces that it was established in 1890. Its old world charm is confirmed by the Burma teak wood fittings, the light ash terrazzo flooring and the grandfather clock at the end of the store. Packs of shirts, kurtas, vests, briefs and other male clothing are neatly stacked in tall wood and glass cabinets on either side; a long counter runs through the middle, like a road divider, displaying more merchandise. Outside, Ibrahim Saheb Street is a converged, single mass of pedestrians, hawkers and vehicles. But for long periods in recent years, the street has been deserted, recalls Ateeq, a sixth generation member of the family that owns H.L. Stores.

It started with the Covid-19 pandemic, which was destructive for offline retail. When things finally reopened, Commercial Street was shut because of repair work. And then Ibrahim Saheb Street itself was dug up and made practically inaccessible. The setbacks were chastening; they jolted H.L Stores, a digital holdout, to finally get serious about the online channel.

It helped that Ateeq, who previously worked as an engineer for twenty five years, joined the business in 2021. Ateeq runs Maxim Outfits, the women’s clothing store adjoining H.L. He had seen many businesses come and go but until the pandemic he never believed his family business would be threatened. Although it had practically no online presence, its name recognition was so strong among old Bangaloreans, it didn’t need to. Now, he acknowledges that even H.L. and Maxim will have to adopt an omni-channel mode. “My store will continue to be my base where I sit and do business but I will also need to do online marketing and sales. We can’t go back to the old model,” he says.

In September, Ateeq signed up with magicpin, his first big move towards adopting a hybrid model, a mix of hyperlocal and online presence via magicpin. So far he’s seen a nice uptick in customer visits and new business. “The biggest benefit is that I get a new footfall from magicpin, and it’s not just like someone seeing an ad in the newspaper. They’re buying my product. Some of them are already becoming repeat customers,” Ateeq says.

Ateeq, co-owner of H.L. Stores, with his brother

Despite the seeming ubiquity of apps and digital products, offline businesses like H.L., in fact, have few options to build a strong online presence. They can advertise on Google or Facebook to attract new customers. But they are understandably wary of spending their limited budgets on platforms where conversions seem elusive and difficult to track. Digital marketing – with its language of Clicks, Cost per Click, CpM and so on — is alienating, too.

Two mins away from H.L., in another by-lane, Faizan runs Bag Planet, a fashion accessories shop. It’s one of his four stores in the Shivaji Nagar neighbourhood. Faizan is a 25 year veteran of the accessories business. His retailing knowhow, extensive sourcing network and access to capital ensured that he continued to thrive initially even after the advent of e-commerce. But over the past few years, his margins have declined as he’s forced to keep lowering prices to attract customers spoilt by the likes of Flipkart and Amazon. Competition within Shivaji Nagar and Commercial Street has intensified too — in Faizan’s informal estimate, the number of shops around Commercial Street has increased four times over the past two decades.

To cope, he’s rented bigger shops, stocked a wider variety of products, and trained his staff to be ultra solicitous even with customers who just come and browse. Still, business remains taxing and complex, uncertainty and anxiety, an everyday experience. “It’s a big problem. We’re spending more and making less,” Faizan says.

Faizan was thus primed to accept when he received a call from the magicpin sales team a few months ago. He had heard of the app and immediately signed up after being assured that the company would diligently respond whenever he had issues. Over the past two months, several hundred customers have come through magicpin to Faizan’s stores. The deals are so attractive that some customers come from as far as 40 km away. “If it wasn’t for magicpin we wouldn’t have these customers. If we hadn’t signed up, that much business would have been lost. Simple,” Faizan says.

Another benefit for Faizan is that magicpin customers come directly to his store unlike walk-ins, who are far more difficult to convert. “What happens on Commercial Street, people walk around and go to many stores (to compare prices and merchandise). But through magicpin, we get customers directly. They don’t have to go to other places,” Faizan says. Because of the new business, he’s been able to rotate products quicker. “You don’t want products stuck for months and months,” he adds.

Bag Planet’s Faizan

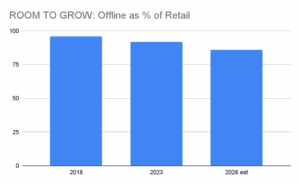

Millions of entrepreneurs like Faizan and Ateeq constitute the vast mainstream of India’s retail market. Cheap smartphones, fast internet and a glut of content have led to cognitive dissonance when it comes to thinking about retail in India. Despite the lightning growth of e-commerce and all things digital, people still do most of their shopping offline. E-commerce accounts for a low single digit share of overall retail and estimates show that even by the end of the decade that share will increase only to the low double digits. That implies $1 to $1.3 trillion will be spent offline annually.

What is undoubtedly changing, however, is the way people shop offline: from cultivating tastes and preferences to discovery and the actual acts of browsing and buying, shopping is undergoing a transformation that is still in its infancy. This is where small retailers need help: enter magicpin.

Source: BCG

“Retailers want to be part of the online journey of their customers but unlike pure online retailers they don’t have the right tools,” magicpin co-founder and chief executive officer (CEO) Anshoo Sharma says. “On magicpin, they showcase their products and services to the local ecosystem of users and get them to their stores to transact.”

While shoppers aren’t as worse off as merchants they, too, lack a sophisticated discovery platform for offline shopping that provides a high-quality experience and cost savings. It’s a yawning gap especially when one considers the fact that for e-commerce there is a plethora of high quality apps like Amazon, Flipkart, Zepto, Blinkit and others.

“People are consuming lots of content online, but they are spending offline. So it’s all but natural that there is an online gateway, a guide, a starting point for their offline journeys. We bring the local markets alive on their smartphones,” Anshoo says.

Even by the standards of internet startups, magicpin’s journey has been dramatic, marked by uncommon perseverance. It started out as a hyperlocal commerce platform before being forced to pivot during the pandemic as the lockdown threatened to make its services redundant. Today, the company is a fast-growing super app that is generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues and is close to profitability. Apart from being the sole recognised online-to-offline player (O2O) in India, it has emerged as a serious challenger to the dominant duo of Zomato and Swiggy in food delivery. magicpin has also established itself as one of the most prominent platforms on the government’s Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) that is transforming commerce in India and is now the largest seller app with 1.5 lakh daily food and logistics orders.

Anshoo and his co-founder Brij Bhushan started magicpin in 2015 with a simple idea: enable offline commerce.

It was a golden period for Indian startups. Budget smartphones were being lapped by Indian consumers, and mobile internet speeds and consistency were improving. The newly elected Narendra Modi-led government had promised to cut red tape, welcome foreign investment and create a supportive environment for technology companies. The Indian economy, already one of the fastest growing in the world, was only going to become stronger, it seemed.

Anshoo and his co-founder had worked as consultants at Bain and were up-and-coming venture investors. When they decided to become entrepreneurs they were certain that their best shot at success was to play in a huge market. In India, none was bigger than retail and during his tenure at Lightspeed, Anshoo had seen large outcomes within hyperlocal retail in international markets.

Some startups had tried their hand in the space; Snapdeal, for instance, in its early avatar sold coupons for stores before pivoting to an online marketplace. Around the time magicpin launched, Groupon India and Little, another hyperlocal deals app, were also operating in the market. But there were early signs of how difficult it would prove to achieve product-market fit: Groupon gave up on India in 2015 after years of effort and significant capital investment. The message was clear: the market was huge, untapped and ripe for invention but it was also insanely complex and challenging.

Initially magicpin persuaded customers (college students were a majority of early users) in its home market of Delhi to upload their selfies and bills at local stores onto the app. The social commerce approach built high engagement levels with users, who received reward points they could use at other local stores. “Pin a location on the map, and we’ll show you the magic,” that was the idea, as Anshoo describes it, behind the magicpin name and its promise to consumers. The user posts served as proof to its restaurant and retail partners that magicpin was indeed driving traffic and business to them. Within two years, it signed up more than a million users across NCR, Mumbai and Bengaluru. Some 50,000 merchants were on the platform, many of them paying a subscription fee.

From the early days Anshoo ran magicpin as a capital efficient startup, a supremely rare feat in the era of hyper-funding. By the middle of 2017, it had raised just $10 million mostly from Lightspeed and Waterbridge, while two of its rivals Little and Nearbuy had received $50 million and $20 million, respectively. Little and Nearbuy were both acquired by Paytm in cut-price deals later in 2017. But magicpin went from strength to strength.

Anshoo Sharma

“We’ve been very deliberate right since our inception around getting economics to work. It needs to work for the consumer, it needs to work for the merchant, it needs to work for us. We’ve always said that we need engagement, we need monetisation, and we need margins,” Anshoo says.

A key element of this approach is that the company’s merchants only pay magicpin a commission on actual sales, not traffic generation. Unlike Google or Facebook, which offer marketing services and drive traffic but offer no revenue guarantee, magicpin only earns revenues when merchants make a sale. That results in incentives being aligned and makes the system tick.

“Our core proposition is very merchant-centric, which is all about being able to entice consumers with attractive offers to walk into the merchants’ stores and buy products,” Lightspeed’s Vivek Gambhir, a magicpin board member, says. “Because merchants only pay us once the conversion happens, it becomes almost a risk free proposition for them.”

This focus on ensuring that its entire ecosystem benefits substantively and consistently ensured that magicpin survived the bloodbath in O2O that had consumed others in the space. Anshoo learnt that the complexity and diversity of offline retail demanded an unusually thoughtful, judicious approach that was alien in the era of chasing growth at all costs. magicpin focused on creating value for merchants, who were far more difficult to please than consumers. As word of mouth about magicpin spread among restaurants, fashion outlets, spas and all kinds of stores, the company saw rapid growth over the next three years.

Towards the end of 2019, magicpin hit the landmark of $1 billion in gross merchandise value (GMV). More than five million consumers and hundreds of thousands of retailers were on the app across 40 cities (although the metros accounted for a majority of the GMV). Apart from local neighbourhood stores, it had attracted the biggest retail brands like Shoppers Stop, Croma, Levi’s, McDonald’s and many others.

In the second week of March 2020, Anshoo wrote a celebratory note to his board. “I said, ‘We’re doing exceptionally well. We just had our best month ever. Acquisition of merchants is working, acquisition of users is working. Our burn rate is going down.’ And so on. All the good things that you’d want as a startup,” he recalls. The company had been in advanced discussions with investors to raise its next round of funding to supercharge its growth. It had already received concrete interest and was confident of closing the round soon.

Barely one week after Anshoo’s note, India announced a brutal nationwide lockdown in response to the pandemic. It was an unprecedented move in modern times: all of retail, with the exception of grocery stores, pharmacies and some other essential services, was shut down in one fell swoop. An economics expert described the situation as “worse than war.”

For a few weeks, the world became chaotic and uncertain in a way that most people had never experienced. For magicpin, it meant literally having to find a new purpose for existence. Its business of connecting consumers with their neighbourhood restaurants, fashion outlets, spas and other offline stores was made to vanish overnight. Fortunately, magicpin did have a few grocery stores and pharmacies on its platform while its restaurant partners were allowed to deliver food.

“If you had asked me when Covid happened, which among our companies might not emerge out of it on the other side, I would have said: magicpin; their revenue fell 90%,” recalls Lightspeed’s Bejul Somaia, who led the fund’s investment into the company. What boosted Bejul’s confidence in magicpin’s ability to survive was that it reacted instantly to the new reality. Even before the lockdown was announced, it switched to super-frugal mode, dramatically reduced costs and explored other options to serve its customers.

Although their core business was temporarily redundant, Anshoo and the team decided that they would keep merchants and consumers at the core of their mission. Customers were stuck at home, but they needed bread, butter, soap, medicines and all kinds of other essentials, preferably delivered to their doorstep. Online quick commerce was in its infancy; the retailers best positioned to serve consumers were neighbourhood stores. But they were used to splitting their orders between walk-ins and phone calls. Now, most people were calling in or wanted to order online. Retailers, however, lacked the technological tools to take detailed orders at scale from customers digitally.

The magicpin team, which was in touch with its merchants, heeded the call. Despite having a near-empty bank balance and lacking experience in building operations, Anshoo decided to build an ordering system for merchants. magicpin would provide an order management system for its retailers that would enable them to take orders, process payments and conduct marketing activities. It would also connect them to third-party logistics players. Apart from groceries, magicpin enabled deliveries of food and medicines. “They were not at all defensive about fundamental business model questions and very open to doing whatever it took to get through. There wasn’t a, ‘We can’t do this, we can’t do that’ mindset,” Bejul says.

To increase adoption, the company didn’t charge commissions initially. Retailers responded with gratitude; the service was sorely needed and it would cost them little. magicpin thus came upon the business that would allow the company to get through the pandemic. In the process, the company not only saved itself but discovered a new capability that would add a transformative engine to its business a few years later.

Bejul had seen the magicpin team prove their superior operational chops and capital efficiency. He was sure that once the lockdown ended and stores reopened, magicpin would remain a vital O2O service. But it was finally the team’s ability to survive disaster with speed, innovation and pluck that convinced him to continue backing the company. Along with Samsung Ventures, Lightspeed and Waterbridge provided the funding that allowed magicpin to stay afloat. The company had to accept a lower valuation than the number it had wanted just weeks ago, but it lived to see another day.

“When we have conviction behind a founder in a market, there are many examples like OYO or Indian Energy Exchange, where the firm and I have stood behind them through turbulent periods. But, look, at the end of the day, you can only do that when there’s a business that’s working. And magicpin got the business to work,” Bejul says.

As the lockdown eased around the middle of 2020, offline retail started to reopen. Tired of staying at home, customers also began to venture out again, albeit cautiously. Both retailers and customers found that magicpin’s original raison d’être — enabling local commerce — was as compelling as ever. The worst had passed.

magicpin rode through the pandemic with what Anshoo, using his old consultancy lingo, calls the double engine: the original service of bringing users to offline stores, and the newer business of enabling home delivery from grocery stores, restaurants, pharmacies and other retailers. The offline business would take some more time to normalise because some customers were still wary of stepping out. But with the double engine, magicpin looked a wiser, more resilient, more diversified business than the young, wide-eyed company that had entered the pandemic.

magicpin’s progress soon caught the eye of Deepinder Goyal, who had pulled off a spectacularly successful public listing of his company, Zomato, in July 2021. Deepinder had already agreed to sit on magicpin’s board and share his insights with the magicpin team on building a great consumer internet startup. In November, Zomato led a $60 million round into magicpin. Announcing the round, Deepinder said, “What Zomato did with restaurants, magicpin is doing for the entire offline shopping experience.” That was high praise, coming from one of the pioneers of the consumer internet ecosystem.

Within 18 months, however, magicpin would do with restaurants exactly what Zomato did with restaurants.

In late 2022, Anshoo met Open Network For Digital Commerce (ONDC), the Indian government’s effort to offer e-commerce services to all kinds of retailers, big and small and Anshoo was instantly struck by ONDC’s determination to scale.

One of ONDC’s main priorities was to bring users to small merchants online and break the stranglehold of one or two large apps in spaces like online retail, food delivery and cab bookings. magicpin with its large merchant network was an ideal fit for ONDC. The open platform was not only keen to sign up magicpin but also to persuade the startup to bet big on its vision.

Anshoo spoke with other entrepreneurs like Vijay Shekhar Sharma and Bhavish Aggarwal, all of whom seemed excited by ONDC’s potential. As importantly, magicpin’s restaurant merchants were eager for alternatives. Zomato and Swiggy dominated food delivery and both companies had been jacking up their commission rates to boost their profitability. Since the platforms brought so much business, restaurants had to pay up; they felt squeezed and helpless. Although ONDC was new, its network of consumer apps was growing as Paytm, Ola, Google and others were signing up. The network could potentially bring millions of new users to magicpin merchants. The opportunity seemed inviting. Anshoo decided to take the plunge and build food delivery on ONDC.

“There is a large value segment that is under served in the food delivery space. Local merchants find it hard to get visibility on large food aggregators and the price points are high for a major segment of Indian consumers. This opportunity in the mass market is what magicpin went for”, said Anshoo. “For local value merchants, magicpin has become the preferred platform for demand generation. Our delivery distances are shorter, allowing us to provide both lower cost of food items as well as lower cost of delivery. This opened up a new market beyond what was being served by the incumbents”, he further added.

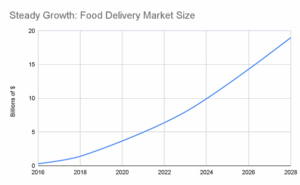

Although magicpin had been running a delivery platform for its merchants for nearly three years, the question nagged at Anshoo: what if it didn’t work out? Yes, the prize was huge: the online food delivery market may touch at least $17 billion by 2028, according to Redseer. But taking Zomato and Swiggy head on was daunting. They had vastly more capital, a fact magicpin knew intimately. Whereas magicpin was built painstakingly, with capital efficiency a tenet and a necessity. If the company were to bet big on food delivery it would take up a huge chunk of its cash reserves.

Source: Redseer

Anshoo decided to test the waters and titrate accordingly. In early 2023, his technology team assigned an intern to integrate magicpin’s platform for food delivery on ONDC. But even after the integration was completed, nothing happened. It turned out that the partner apps on ONDC hadn’t built out their customer journeys. Such teething troubles were common for a new network. magicpin worked with the partner apps to put in place the technology layers for customer journeys. This was key since experience would suffer if there were drop-offs in any leg of the user journey from the first click right until the payment. By owning the technology layers, magicpin finally had the ability to deliver a seamless experience. In the summer of 2023, on the back of its large offline network, magicpin was able to launch on ONDC with as many as 22,000 restaurants.

The food delivery ecosystem — customers, restaurants, delivery players, other ONDC apps — enthusiastically lapped it up. magicpin went from delivering a few hundred orders a day in April 2023 to 10,000 orders a month later, and some 20,000 within five weeks to now an average of 1.5 Lakh orders each day for food and logistics.

Swiggy and Zomato have built a terrific ecosystem for food delivery but magicpin is giving them “a run for their money,” according to Vikash Prasad, partner at Bengaluru’s Meghana Biryani, one of the biggest restaurants in India in food delivery.

From the early days it became clear to Vikash that magicpin was a serious player. He recalls that a couple of early problems he faced with magicpin were addressed remarkably quickly. One, the delivery staff were arriving in advance and waiting at Meghana outlets for orders to be prepared, which drove down efficiency; two, while taking on multiple orders simultaneously, delivery staff were sometimes handing them over to the wrong customer. But, after feedback from Meghana, magicpin resolved these issues within weeks. “It showed that they’re basically receptive to their partners and their partners’ problems,” he says.

Meghana Biryani’s Vikash Prasad

It’s not just the big players like Meghana, magicpin’s entry has been a boon for smaller restaurants and cloud kitchens too.

Arko Banerjee, founder of Bengali food cloud kitchen Gimni’s Kitchen, agreed to work with magicpin some 18 months ago after a company salesperson reached out. He was satisfied with Swiggy and Zomato, but was open to adding to his options. Since he signed up with magicpin, his daily business has increased over 5X. Not just that, because magicpin’s commission rates are much lower than the rivals’, he has been able to sustain the quality while keeping costs under control.

Apart from the attentiveness of the company’s sales team, Arko loves its merchant product. “What I find very intuitive are their dashboards on new customers, comparisons (with other restaurants in the area), the ranking, the insights they give on performance. The charts are beautifully presented. It stays in your memory,” Arko says. He regularly puts his magicpin restaurant ranking as his WhatsApp status. “It’s a motivation as a business owner, right?”

Like restaurants, customers also say that magicpin is a much-needed addition in a space where the incumbents are continually increasing prices.

When Sahil, who works as a senior manager at a healthcare firm in Gurugram, heard of magicpin from his friend about 18 months ago, he was a loyal Zomato customer (who also used Swiggy). Now, before placing any order, he typically compares prices across the three apps. He estimates that over the past six months, on average, he’s ordered on magicpin 8 out of 10 times. “All the three apps give a very good customer experience but magicpin usually has the best prices,” Sahil says.

Apart from lower prices, he observes that orders tend to be assigned to delivery workers quicker on magicpin. He likes that magicpin has small, local restaurants that aren’t available on other apps. “The big restaurants are on all the three apps, but I usually order Mughlai food and magicpin has local joints that won’t be there elsewhere,” Sahil says.

That small, local restaurants are available on the app is no accident; it’s an important feature of magicpin’s approach. The company partners with even smaller merchants like chaat and street food vendors. It has a target of bringing on board 500 street vendors (the only requirement is that they must be registered with the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India). This is in addition to the 100,000 merchants it pledged in July to add on ONDC.

In October, magicpin reached a milestone: it became the largest food delivery app on ONDC. The company registered 150,000 food delivery orders a day in 2024. Anshoo said then that magicpin had “touched double-digit market share in major cities, with more than 10 per cent market share in key markets like Delhi or Bengaluru in terms of overall food delivery.”

To understand the scale of magicpin’s achievement, consider this. Swiggy took as long as four years or so after its launch and hundreds of millions of dollars in capital to reach 150,000 daily orders. magicpin got there within 18 months of launching on ONDC, having raised a little more than $100 million (which was mostly deployed in the O2O business, not food delivery).

Apart from magicpin’s operational and technological excellence, what has helped the company is the knowledge bank built up by the food delivery ecosystem, Meghana Biryani’s Vikash says. “I told Swiggy and Zomato that it took you 10 years to reach here, but magicpin might even do it in 20% of that time, because the problem solving ability of the whole ecosystem will just keep getting better,” he says.

For Vikash, it’s “extremely important” that magicpin succeeds: it gives him better bargaining power as a restaurant. “You need more players for a better market. I think India is big enough for another one to two more players in the food delivery & logistics landscape.” Vikash says.

One of the things that makes restaurant partners such as Meghana care deeply about magicpin’s success is that unlike the other platforms magicpin has no intent of opening cloud kitchens. The company is clear that its role is to support and grow the businesses of its restaurant partners, not to compete with them. Instead of the hybrid model that has become the norm in online commerce, magicpin is fulfilling the original promise of a marketplace, that of connecting buyers and sellers, customers and restaurants. In an environment where internet platforms’ own offerings — be it private labels in online retail and grocery delivery or cloud kitchens in food delivery — drive their own sellers and partners out of business, magicpin’s firm stand on avoiding opening cloud kitchens only boosts its standing as the third front in food delivery.

Scaling food delivery has also allowed the company to launch another business. For its large restaurant partners like KFC and Rebel Foods, which deliver some of their orders directly to customers, magicpin offers a hyperlocal logistics service through which they can book third-party delivery providers. magicpin’s logistics technology arm, magicFleet was built to bridge a critical gap in India’s last-mile delivery infrastructure—by providing micro and small logistics entrepreneurs access to a tech-enabled operations stack and steady demand through ONDC and magicpin. It has crossed a significant milestone by onboarding thousands of riders in under eight months of its launch. Designed as an AI-powered SaaS platform, magicFleet is fast emerging as a key enabler for India’s decentralized commerce ecosystem, particularly through its deep integration with the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC).

magicpin’s success in becoming the No.3 app in food delivery in little time is eventually a testament of Anshoo’s entrepreneurial instincts.

Lightspeed’s Bejul, who had hired Anshoo at the fund from Bain, observes that the magicpin CEO made the high-risk ONDC bet when there was no data, no evidence that the network would scale. He recalls that the Anshoo he knew at Lightspeed was “very measured, very analytical,” and “wouldn’t paint too much outside the lines,” just like a former consultant; but that’s changed dramatically at magicpin.

“Most consultants will reason their way into something, and typically reasoning requires some data. The problem is that for things that haven’t happened yet there’s no data. That’s one of the things great entrepreneurs do very well. They trust their instincts. They see opportunities where other people may not and then they go execute against it,” Bejul says. Execution involves delivering through other people, and Anshoo has grown to excel at that. “It’s been very energising to see Anshoo actually make that journey. His mindset is more of an operator than a VC’s,” Bejul says.

magicpin’s execution muscle has been built through rigorous processes. To start with, Anshoo conducts a detailed briefing with his lieutenants every morning and covers all the key aspects of the business from merchant experience and operations matters to customer experience and personnel issues. Every day, the P&L is closed, an uncommon characteristic at a startup. “By the end of the morning calls, what has happened is that I know what is working, what is not working. People who are responsible for those are also aware of what is working and what is not working. And the organisation’s priorities are very clearly aligned,” Anshoo says.

Anshoo has set up the organisation to be “very outcomes oriented” across functions. In many companies, the technology team is set up to support business. But magicpin’s engineers are directly responsible, in part, for business metrics. If merchant cancellation rates increase or customer conversion rates drop, the tech people in charge of the respective product are accountable, not a product manager.

“I’ve found this to be phenomenal leverage because tech is usually the most scarce resource. If you put tech in a position where they are service providers, then everyone’s going to stand in a queue. But if you make them the drivers, then the whole thing looks very different. It leads to everyone being able to talk the same language generally,” Anshoo says.

While its food delivery bet is on track to become a massive win, the company’s core business remains the O2O service. Scaling food delivery, in fact, makes O2O more attractive for customers, and also for many of the company’s merchants.

Sahil, the healthcare manager in Gurugram who has become a frequent magicpin food delivery customer, uses the reward points he gains from his food delivery orders for other categories like restaurant bookings and cosmetic shopping. “It’s really good to have offline and online (services) on the same app. When you go on Zomato you can only order food or see restaurants. magicpin has a lot more options. When you get multiple options you end up buying a lot of things and don’t need to go anywhere else,” Sahil says.

Sahil’s customer journey illustrates magicpin’s game-plan; offer a high-use case product like food delivery, which keeps customers coming back to the app and makes it more likely that they will use it for its offline services.

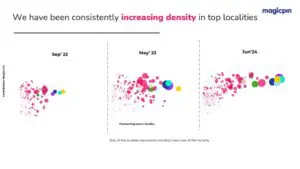

Through the pandemic, the company effected a change in the way it approaches the O2O business. Before Covid-19 it had focused on expanding to a large number of cities. But a key lesson it learnt is that maximising density — capturing as many local commerce transactions as possible across categories — in high-value neighbourhoods like Koramangala, Indiranagar and Lajpat Nagar is better than spreading itself thin across many cities. Accordingly, the company now aims its efforts at capturing an increasing portion of all retail transactions that are conducted in a select number of high-value neighbourhoods (overall, it is present in roughly 6000 neighbourhoods across 20 cities).

“When a locality becomes dense, it attracts more users because there are more merchants, and it attracts more merchants because there are more users. The more we are penetrated in a micro market, the more merchants would want to be on the platform, and the more they’d be willing to pay. They want to do better than their neighbourhood rivals and being on magicpin enables that,” Anshoo says.

In short, high density in targeted neighbourhoods, not necessarily spread, begets the tremendous benefits of network effects.

magicpin’s expanding neighbourhood density (the bubbles represent neighbourhoods)

At present, restaurants and fashion stores, including clothing, footwear and beauty shops, are the biggest draws for magicpin customers. But the company is also expanding its medicines, groceries and entertainment categories. Again, this flows from the idea of maximising its share of local commerce.

“When people go to a particular market, they don’t just buy one thing. Maybe they buy some apparel, some shoes, they’ll eat something. So the vision is that when you’re going out to shop, for every single thing you buy, you can use magicpin,” Lightspeed’s Vivek Gambhir explains.

No doubt, it’s an ambitious vision: magicpin essentially aims to mediate and shape consumers’ experience of commerce in the real world. It means nothing less than the cultivation of a new habit among consumers, a new way of experiencing their localities. In practice this involves leveraging technology to showcase attractive products and deals on the app and designing offers and points-based rewards that keep customers hooked and deliver substantial cost savings.

“The three things we communicate to customers are: product, price and place. Earlier, we used to hook people on engagement and get them to do commerce. Now we’ve turned it around to make commerce engaging,” Anshoo says.

He elaborates, “Let’s say a user has a certain number of points. We say that if you earn a few more points, you can get this gulab jamun at one rupee from your local store, either home delivered or at the shop. Similarly, there’ll be great offers on fashion, bars, entertainment, etc. Basically, users are rewarded for being loyal to the app, for opening it regularly.”

A typical magicpin user conducts three to four transactions, on average, every month. With the continuous addition of merchants and the increasing refinement of app features like scratch cards and reward points, that number is on track to rise significantly.

magicpin’s horizontal O2O model is unique within India but there’s evidence in other countries that such an approach works. A case that highlights the value of a more direct marketing platform for merchants compared with conventional digital channels is the e-commerce giant Amazon. In the US, Amazon, with its dominance in online shopping, has emerged as the biggest threat to Google and Facebook for digital advertising spend. Many shoppers now directly visit Amazon to search for products that they desire. Brands and sellers are increasingly acknowledging the potential upside of advertising on a platform where users’ intent to buy is more serious and advanced than on search engines and social media.

But the most pertinent example that showcases magicpin’s potential is Meituan, the Chinese super app that has transformed how local commerce is conducted in Asia’s largest economy. Meituan started off a group buying coupons business and later added food delivery (through a merger), travel, ride sharing, entertainment and other services. Over time, Meituan also began to deliver groceries, fashion and other products from local merchants to customers. Today, it is the largest food delivery and O2O app in China with a market capitalisation of $130 billion.

magicpin’s numbers indicate that the company is well positioned to realise its vision of becoming India’s hyperlocal commerce powerhouse. Its revenues have been soaring for years while its cash burn has significantly declined over the past two years in particular. According to its latest audited results, magicpin recorded a revenue of ₹870 crore in FY24, nearly three times the previous year’s figure. Its net loss was down 25%. Since then, the double engine has continued to see sustained growth even as the core retail business is close to generating cash.

And unlike many other platforms, magicpin is going about its journey not by gaining at the expense of its partners, but by carrying them along. By doing so, the company is standing up for India’s storied retailer community, delivering on its promises and reshaping what support looks like in India’s hyperlocal economy.

“We have to aspire to greatness. I’m not saying we’ll have it, but there is room for it. We know how to run a high quality company. We’ve found something valuable that we worked very hard to get. It should be a lot more fun as we continue to build from here,” Anshoo says.