News

Founder stories,

partner perspectives,

and industry insights.

Deepening Our Partnership With Anthropic

True tipping points in technology are rare. Over the past few decades, we’ve witnessed the rise of software, the internet, the cloud, and mobile, each wave reshaping how companies operate and how people live. The impact has been extraordinary but so too was the noise that surrounded them, as the technologies matured and the true winners emerged.

AI is different. Its potential to transform our lives is even more profound. As the past three years have shown, the pace and intensity of change have been almost relentless. Amid this whirlwind, Anthropic has stood out as a steady force. Their mission is simple yet powerful: to scale intelligence that is both trustworthy and safe. The team’s execution against that vision has been exceptional, and it’s why we’re proud to deepen our partnership with Anthropic in their Series F.

Singular Focus – Clarity in the Chaos

Amid the daily noise in the AI world – Anthropic’s vision has remained simple and clear from the beginning:

- Scaling Intelligence: Anthropic’s team has been laser-focused on advancing frontier foundation models, driven by the conviction that core model performance, not “application scaffolding”, is the key to unlocking new capabilities. When the world seemingly panicked as DeepSeek launched their models in early 2025, Anthropic stayed disciplined pushing forward on the fundamentals of advancing intelligence.

- Safety & Reliability: Anthropic’s obsessive focus on safety and reliability is more than good citizenship – it’s their ultimate competitive advantage. At some point we’ll see a “WannaCry moment” in AI, just as the 2017 ransomware attack forced enterprises to take cybersecurity seriously. When it comes, the world will demand the safety and alignment capabilities Anthropic has been building since day one.

- Enterprise: Anthropic’s enterprise focus flows directly from its priorities on responsibly scaling intelligence so it is both powerful and reliable and safe. Nowhere else is trustworthy intelligence more valuable than in businesses and government institutions. For these stakeholders and institutions safety isn’t theoretical. It’s existential. We believe Anthropic’s mission-driven approach to safety makes them a natural and valuable partner in the enterprise market.

When Focus Meets Opportunity

When a clear strategy meets an opportunity of unprecedented scale, the result is adoption at a speed rarely seen in history. At the start of 2025, fresh off their Series E, Anthropic had already reached run-rate revenue of ~$1B, less than two years after publicly launching their first model. Today, the company has surpassed $5B, making Anthropic the fastest growing technology company ever.

This growth is a direct result of scaling intelligence. Each leap in model capabilities, unlocks new use-cases and opens trillion-dollar markets for innovation. We are now seeing this acceleration across healthcare, legal, financial services, biotech and drug discovery, and nearly every type of knowledge work.

Nowhere is this shift clearer than in software development. Over the past 18 months, Anthropic’s models have gone from simple code completion to more than seven hours of independent, autonomous coding. Claude’s agentic coding product, Claude Code, has grown from research preview to >$500M in run-rate revenue in just three months. Claude Code exemplifies the paradigm shift underway – while apps package existing capabilities, it is core model intelligence that creates new ones. The value is in the model.

Our Partnership: Backing the Future

For over two years, Lightspeed has backed Anthropic’s singular mission through three consecutive investments. We believe they represent the rare combination of incredible ambition, technical excellence, and unwavering commitment to beneficial outcomes.

Anthropic’s talent-dense team understands that intelligence matters more than features, depth more than breadth. Their technology aims to enhance our public institutions, supercharge economic activity across enterprises, and help individuals solve their most complex problems.

As frontier AI advances exponentially, Anthropic is positioned to become one of the most transformational companies of our generation. We’re proud to support them on this journey to scale intelligence for the benefit of all.

The content here should not be viewed as investment advice, nor does it constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities. Certain statements herein are the opinions and beliefs of Lightspeed; other market participants could take different views.

Discover Lightspeed AI research and features

Every day brings something new in AI, and sorting the noise from what actually matters can feel like a massive undertaking. We channeled our expertise as builders, investors, and operators to help you navigate the trends and breakthroughs shaping the future. Through market analysis, insights from our portfolio, and conversations with top researchers, our goal is to give you a clear view of AI today and where it’s headed tomorrow.

Lightspeed Announces Lead Investment in Anthropic’s $3.5B Series E Financing

Anthropic’s trajectory over the past three years has been remarkable. Founded in 2021 by a team of seven with a shared vision for building AI that’s both safer and more capable, Anthropic has rapidly pushed the boundaries of what artificial intelligence can achieve.

Lightspeed first engaged with Anthropic in early 2023, when the company had fewer than 100 employees, no public product, and was pre-revenue. In the two years since, Anthropic has launched industry-defining models, forged major partnerships with industry giants, and scaled at a striking rate.

Today, Lightspeed is deepening its commitment to this vision, by leading Anthropic’s $3.5 Billion Series E as the largest investor in the round. This round underscores our conviction in Anthropic and the essential role of foundation models as the bedrock of AI progress.

An Era-Defining Rise

True tipping points in technology are rare. Over the past few decades, we’ve seen software, internet, cloud, and mobile fundamentally change how companies operate and how people live their lives.

But while these shifts were transformative, they were mostly platform shifts. They enabled new experiences, but not fundamentally new technological capabilities. Software became much cheaper and scaled to every corner of our lives, but most disruptions did not feel like true tipping points. Mobile experiences, while more pervasive, are not fundamentally more powerful than desktop capabilities.

AI — intelligence as software — is a fundamentally different paradigm. We are witnessing the creation of novel capabilities that simply did not exist before, and they are transforming domain after domain.

Language models have started to disrupt content creation, coding, analysis, education, customer support, knowledge and database management, decision support, creative collaboration, and many more areas of human activity — all now available as a service.

Self-driving cars are rapidly scaling across cities worldwide.

Entire disciplines of research, including protein folding, materials science, and synthetic biology are starting to be transformed or disrupted, compressing hundreds of years of scientific discovery into mere months.

We see no evidence that this pace of innovation is slowing. In fact, we think it may be accelerating. Improvements in the architecture of algorithms, in reinforcement learning and in post-training are improving the core capabilities of AI models, while improvements in test-time compute and chain-of-thought reasoning are spawning a new generation of models that can reason their way through problems in real-time in much more systematic, human-like ways. This is leading to compounding, exponential improvements in AI’s capabilities at the frontier.

Anthropic’s rapid rise illustrates these trends well. When Lightspeed first engaged with the company in January 2023, it did not yet have a public product.

But in the two years since, Anthropic has:

- Launched four major generations of its flagship product, Claude, that have leapfrogged the state of the art in AI’s core capabilities — the most recent release of Claude 3.7 Sonnet is the industry’s first generally available hybrid-intelligence model with extended thinking capabilities.

- Announced major strategic partnerships with Google and AWS that surface those capabilities to millions of businesses, and introduced infrastructure tools that transform how AI integrates with business systems, accelerating AI’s rapid rate of adoption.

- Developed protocols and tools that give those AI models access to the data they need, and the ability to use computers like humans do to increase their effectiveness.

- Raised billions to accelerate their R&D and product deployments while expanding their international operations, building on existing global presence in the US, UK, and EU.

We believe the result is the non-linear scaling of intelligence-as-a-service.

Lightspeed has supported Anthropic throughout this journey, including investing in the Series D in early 2024. Our lead investment in Anthropic’s Series E now marks its next phase: a major advance in the next frontier of AI, and an acceleration of its adoption across the enterprise.

Apple’s AI Reasoning Paper: Good Questions, Few Answers

You may have seen a paper out of Apple last month with the title, “The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity”, which caused a bit of a stir. The paper purported to show that:

- The accuracy of reasoning models collapses beyond a certain level of problem complexity.

- The self-reflection and self-correction mechanism of reasoning models are insufficient for general problem-solving.

- Reasoning models paradoxically reduce their “thinking” effort when encountering hard or complex problems.

The implication would be that these reasoning models have critical weaknesses, which will prevent them from scaling to the most complex, longest problems. If true, this would cap the potential gains of the current reinforcement learning-based post-training paradigm.

However, shortly after publication, numerous critiques surfaced that brought into question the paper’s methodology, which I’ll quickly outline below. Suffice it to say, the Apple researchers overreached in the extent of their claims and suggestions. The paper does raise interesting fundamental questions about reasoning models but does not strictly prove the core claims.

What did the Apple paper show?

The researchers set up a number of logic puzzles and varied the degree of complexity up and down for each task, testing model accuracy and compute used (measured in “thinking tokens” outputted). They compared multiple reasoning models (Claude, o3, DeepSeek) along with their non-thinking/reasoning variants.

The accuracy results showed:

- Reasoning models match or outperform non-thinking models for problems up to medium complexity.

- For high-complexity problems, performance for both variants collapses to zero.

Hello, World Models!

At Lightspeed, with firmwide conviction, we continue our thesis of AI as an unprecedented source of value creation—reshaping industries even faster than the platform and architecture shifts we observed during the emergence of the internet, mobile phones, and cloud computing.

To date, we have invested ~$2.5 billion in over 100 companies in the AI technology stack. These portfolio companies offer products ranging from foundation models to AI-native developer tooling and applications in enterprise, healthcare, financial technology, consumer, and gaming & interactive media.

Lightspeed Newsletter, Doubling Down on Anthropic

Recently, we announced Lightspeed’s lead investment in Anthropic’s $3.5 Billion Series E round. Our team first engaged with Anthropic two years ago. At the time, they had fewer than 100 employees, no public product, and were pre-revenue. The company went on to launch industry-defining models, built strategic partnerships with industry giants including Google and AWS, and scaled at an incredible rate. Our core belief at Lightspeed is that the biggest value from the development of AI will be unlocked at the foundation level. The most important applications are still being built, and the models that underpin them are essential to the next wave of AI evolution. So essential, in fact, that we estimate the next wave of AI technologies could power experiences and activities that represent $1.5 trillion in net-new revenue. This new funding ushers in Anthropic’s next phase: a major advance in the next frontier of AI, and an acceleration of its adoption across the enterprise.

Perspective: DeepSeek and Defending American AI Leadership

Over the last week, DeepSeek has grabbed the world’s attention—and for good reason. They achieved something remarkable, despite the constraints of export controls, managing to use creative engineering solutions to train a powerful AI model for just $6 million (for the final training run – more on this later). This is exactly why Anthropic founder Dario Amodei posted a call for tighter export controls. It’s an impressive feat—one that deserves recognition and will undoubtedly inspire further innovation across the broader ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s important to put DeepSeek’s achievement in perspective: it represents a savvy iteration on the first chapter of AI development and scaling rather than the beginning of a new chapter.

A Changing of the Guard: Post-Training over Pre-Training

The previous era was defined by both the scaling and optimization of pre-training. Early progress hinged on massive capital investments in compute and data during pre-training to drive performance gains. Leading labs—Anthropic, Google DeepMind, OpenAI—were focused on creating the foundational recipe for model training. DeepSeek’s success builds directly on those investments and wouldn’t have been possible without them.

Moreover, the focus on the ~$6M *final* training run, even if taken at face value, is misleading since it only includes the cost of the final DeepSeek v3 training run. We suspect the “fully loaded” cost (training the base model, data collection and prep, SFT, RL, various research experiments, etc.) is comparable to the costs of models like Claude 3.5 Sonnet or OpenAI GPT4o.

Algorithmically, DeepSeek focused their post-training regimen on highly scaled RL (reinforcement learning) to produce emergent reasoning abilities. This approach is also well known to US labs who have been working with it for some time now. Perhaps more importantly, US Labs, because of their significant resources, have been focused on researching *multiple* new RL post-training regimens simultaneously, and this, combined with their superior compute and infrastructure resources, is going to be what really unlocks future acceleration in the march towards super-intelligence. DeepSeek certainly delivered an impressive model in terms of its current size and efficiency and competence, but it still hasn’t fully caught up to the highest-performing foundation models. Anthropic’s Sonnet 3.5, for instance, remains well ahead of R1 in its reasoning ability for real-world coding use cases.

The end goal is what really matters. If you are aiming for the moon, building a low-orbit satellite is a distraction. The large AI labs have the singular goal of developing AGI – the real moonshot. We believe that they uniquely have the talent, capital, and capabilities to win.

Getting to the Next Frontier Will Require Large Amounts of Capital…But it Will be Worth it

The leading AI labs have for months been focused squarely on the new RL-based post training regime, and progress is rapid. Today, models like DeepSeek’s R1 will compare favorably on paper because, to their credit, they moved quickly. But more importantly, scaling laws for this new paradigm over the long term will require exponentially more resources in compute and data: resources enjoyed by few companies. The encouraging news is we already know that scaling this approach massively improves the capabilities of the next generation of models, expanding potential use cases in turn, and again widening the current gap between established labs and China’s capabilities.

Enterprises Need More Than a Model

Models are not products, and enterprises building on foundation models need more than just intelligence through an API. As with prior technology waves, they’ll need a set of infrastructure building blocks to support robust development, testing, deployment, monitoring, and governance of their AI applications at scale. Enterprises must care deeply about security, compliance, liability, safety, interpretability, and much more. It is hard to imagine that US companies would be willing to leverage models of questionable origin. Companies such as Anthropic are focused on ensuring they build enterprise-ready products – that’s very different from developing a model that could have security problems, bias, censorship, toxicity, and other issues that haven’t been fully addressed.

How We Win

There is no question that the US’ leadership in AI has caught the attention of other nations. There are legitimate questions amongst the research community about the potential role of unauthorized distillation (i.e. employing methods to extract and copy training data without tipping off the model provider or the model itself).

We’re observing an emerging consensus that DeepSeek’s models were likely trained on Chain-of-Thought outputs from other leading frontier models (against their terms of service). Microsoft and OpenAI are now formally investigating the possible unauthorized exfiltration of large quantities of training data by DeepSeek. Earlier stories echoing this suspicion were reported both by TechCrunch and again in this report by JPMC yesterday.

The time has come for US frontier model companies to urgently prioritize research and development for new AI security measures. This is why OpenAI’s o1 reasoning tokens are shielded from end users. By now, it’s likely that jailbreaks have been discovered to circumvent these rudimentary measures.

Export controls on high-end chips have been somewhat effective at slowing China’s AI development but these controls must be tightened further and robustly enforced. As of today, China is actively working to bypass these restrictions, using shell companies to access advanced chips through third-party countries. This will continue and the new administration needs to be prepared to take further action.

The US *is* where the brightest minds have assembled to drive this generational shift forward. For AI to be safe, secure and trusted, we need AI to be built in the US and for the US and its allies.

This is a race we can win – now we need to do the work to ensure that we do.

The content here should not be viewed as investment advice, nor does it constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities. Certain statements herein are the opinions and beliefs of Lightspeed; other market participants could take different views.

Celebrating the 2025 Game Changers—Adaptation and Resilience

Lightspeed partnered with GamesBeat, Nasdaq, and leading judges and mentors once again to spotlight the 25 most innovative startups reshaping the gaming & interactive media industry.

For half a century, video games have profoundly shaped consumer behavior and acted as a catalyst for significant technological innovation.

As an ever-increasing time of our lives is spent in immersive virtual worlds, gaming is expected to continue its pivotal role in how we play, work, and connect.

And like every industry, the gaming world is defined by outliers — the few companies that push the boundaries and pave the way for how the next generation of games are made and played.

That’s why, after the success of last year’s program, Lightspeed, GamesBeat, and Nasdaq again teamed up with industry-leading judges and mentors to recognize extraordinary startups revolutionizing gaming and interactive media.

This year’s theme: resilience and adaptation

The gaming industry is in constant flux, so this year’s list emphasizes resilience and adaptation — honoring ideas and strategies that demonstrate a startup’s ability to not only withstand the challenges facing the gaming & interactive media industry but excel in this turbulent environment.

In June, we asked the gaming and venture communities to nominate standout startups across five key categories:

- 3D technology & infrastructure

- Generative AI & agents

- Game studios & UGC

- Interactive media platforms

- Extended reality (AR & VR)

To qualify, entrants had to have been in business no more than five years and have no more than 50 full-time employees. The goal of this list is to highlight startups that have unique and original visions with a strong focus on execution.

Introducing the Top 25

After receiving an overwhelming amount of entries (almost 40% more than last year), Lightspeed investors and GamesBeat editors narrowed the list of entrants to 75.

From there, a star panel of judges — including C-level gaming executives and senior operators across companies like Activision Blizzard, Amazon, TikTok, Riot Games, Tencent, and DeepMind — scored each candidate (with ~10 votes per startup). We then took the average scores across all judges for each company, sorted the list, and arrived at our final 25.

Here are our five best-in-category winners.

Best 3D technology & infrastructure: k-ID

There are nearly a billion kids and teens globally that play games online. Yet, today, children pay the price for publisher shortcomings: trolling, cyberbullying, exploitation, toxicity, harassment, grooming, and other forms of online abuse.

The judges were impressed by k-ID’s bold approach in tackling one of the industry’s most pressing, complex challenges — providing a platform that allows both families and publishers to immediately create safe spaces for kids and teens online. At Lightspeed, we believe innovation should drive meaningful and positive change, and k-ID sets that standard, building infrastructure and technology that prioritizes both entertainment and safety. (Note: k-ID is a Lightspeed portfolio company.)

Best Generative AI & agents: Bitmagic

The barrier to create games has always been high. While there are three billion gamers worldwide, there are only ~200,000 professional game developers.

Bitmagic believes anyone should be able to create games.

Bitmagic caught the judges’ attention for its groundbreaking use of generative AI — it’s the first system in the world that leverages generative AI to transform text prompts into fully interactive, multiplayer 3D games. By eliminating the traditional barriers to game development, we see that Bitmagic can act as a catalyst for game lovers, empowering users of all skill levels to bring their game ideas to life with unprecedented ease.

With its recent availability on Steam Playtest, Bitmagic is well underway to democratize game development.

Best game studios & UGC: Giant Skull

Led by industry veteran Stig Asmussen, the mind behind God of War III and the Star Wars Jedi series, Giant Skull is focused on creating AAA, story-driven action-adventure games.

While their technical and visual achievements blew away our judges, our panel was also impressed by the company’s commitment to sustainability practices, work-life balance, and diversity, opting to employ remote developers all over the world.

Best extended reality (AR & VR): Eggscape

Eggscape impressed the judges with its unique blend of mixed reality (MR) and humor, a rare combination in XR.

Known for their immersive VR experiences like Gloomy Eyes featuring Colin Farrell and Paper Birds featuring Edward Norton, Eggscape is an extended reality game where players navigate vivid 3D levels and interact with fellow gamers in real time, all while expecting the relentless invasion of alien robots.

With Eggverse’s world-building tool that allows you to share creations with your friends, its combination of art direction, innovative gameplay, and social connection makes for a new direction in XR.

Best interactive media platforms: Pok Pok

Gaming, especially for young children, can be overstimulating and addictive. Pok Pok stood out with its calm, creativity-driven approach.

Inspired by Montessori principles, Pok Pok prioritizes open-ended, non-addictive educational games for children ages 2-8. Collaborating with the top minds in education, the interactive platform allows children to explore and learn at their own pace.

The minimalist design and thoughtful execution have earned them an Apple Design Award, and highlight a shift in gaming towards more meaningful, balanced entertainment that resonates with both parents and children.

AI Enterprise Market Map: Cutting through the hype

Technology adoption is inherently cyclical, and no technology has gone through more up-and-down cycles than artificial intelligence. After enduring multiple long AI winters, the technology is now enjoying a red hot summer that shows no sign of cooling.

Nearly all of the energy and activity surrounding the technology can be traced to the rise of generative AI — and, more specifically, to the debut of OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3 in November 2022 just 18 months ago. Since then, Gen AI has entered popular culture in a big way, introducing a number of new terms to our vocabularies — including prompt engineers, deep fakes, and AI girlfriends. By now, even your grandparents have heard of ChatGPT.

Though this “overnight sensation” was actually years in the making, its sudden and impactful emergence put some of the world’s biggest technology companies on the backfoot.

Since then, companies like Amazon, Google, and Meta have been racing to catch up, with varying levels of success (and a few notable missteps).

Gen AI’s emergence also opened the floodgates to an entire ecosystem of startups, ranging from large language models (LLMs) to enablement infrastructure platforms and an ever-expanding number of consumer, enterprise, and sector-specific applications.

In short, the AI industry is evolving rapidly. Some of the companies grabbing headlines today may not be around in a few years. Equally, it’s plausible that the startups that will play a formative role in shaping this nascent industry may not yet even exist. Our purpose here is to offer a snapshot of the AI market as it stands today, the factors that we anticipate will shape its future, and where we believe the market is headed over the long term.

The Future of Voice: Our Thoughts On How It Will Transform Conversational AI

A little over a decade ago, the movie Her introduced us to Samantha, an AI-powered operating system whose human companion falls in love with her through the sound of her voice.

Back in 2013, this felt like science fiction–maybe even fantasy. But today, it looks more like a product road map. Since ChatGPT launched 18 months ago, we’ve witnessed step-function changes in innovation across a range of modalities, with perhaps voice emerging as a key frontier. And just recently, Open AI launched advanced voice mode, a feature part of ChatGPT that enables near-human-like audio conversations. As such, we are on the brink of a voice revolution, bringing us closer to the Her experience.

Large Language Models (LLMs) and multi-modal chatbots are radically transforming how companies communicate with customers and vice versa. And at Lightspeed, we’ve had dozens of conversations with researchers and founders who are building the next generation of voice applications. Here’s our take on where the voice market is today and where it’s headed in the coming years.

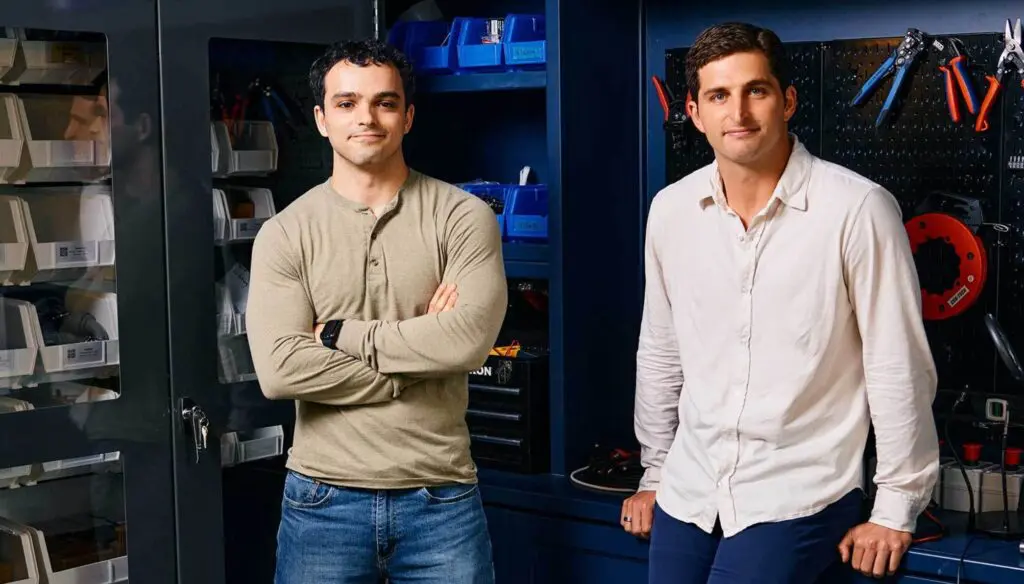

How Rubrik Became A Cybersecurity Headliner

By Greg Sandoval

In 2013, Bipul Sinha appeared well on his way to a stellar career as a venture capitalist (VC). As a partner at Lightspeed, he worked on investments in several promising startups, including Nutanix. And while he enjoyed identifying promising founders and helping them build generational success stories, there was one thing missing for Sinha: the chance to build his own.

In 2014, he and a group of co-founders launched Rubrik, a data security company. During the past year, Rubrik surpassed $500 million in subscription annual recurring revenue (ARR) and celebrated acquiring its 5,000th customer. Lightspeed partner Ravi Mhatre, who backed Sinha when he founded Rubrik, believes he understands at least part of the reason Sinha succeeded against all odds.

“Like many others in this country, he’s an immigrant,” Mhatre said. “He came here with the desire to make the most of his opportunity to be in the United States and to pursue the American dream. He is not someone who will ever choose the cushier road. Successful VCs and entrepreneurs take risks while also embracing opportunities, and that is Bipul.”

“Ravi has been on this journey with us from the time Rubrik began,” Sinha said. “He has a tremendous framework for thinking, in terms of go-to market, choosing talent, and knowing how businesses can succeed. Startups need a specific ecosystem built around investors and board members who have a growth mindset. Ravi helped us create that initial, winning framework.”

Lightspeed As Springboard

Lightspeed became a second home for Sinha, one that allowed him to analyze important markets from a broad industry perspective. At the time, backup and recovery was an established market with plenty of demand. However, the sector had become bereft of new ideas, resulting in little innovation. Meanwhile, data became the engine powering global business. Many companies began seeing rapid growth in data given the shift to digital transformation.

Sinha saw the implications in this trend, reckoning that anyone who could pioneer new methods to help businesses better manage their data and extract greater value from it would stand to benefit immensely.

To that end, Sinha teamed with Arvind Jain, Arvind Nithrakashyap and Soham Mazumdar and they went to work to create a blueprint for a disruptive, flexible backup-and-recovery platform built for cyber. Lightspeed also began finding ways to contribute that extended beyond providing capital, though it provided that too.

To date, Lightspeed has invested a total of $362 million in Rubrik.

“Lightspeed helped us tremendously in validating our idea,” Sinha said. “With Lightspeed’s live stream ecosystems, we went to technology buyers and got their feedback on how the product could be delivered, and how they planned to use it. A lot of initial validation happened within their ecosystem.”

Finding Rubrik’s ‘Killer App’

Sinha acknowledges that he and his co-founders knew that Rubrik’s original product wasn’t sufficient on its own to create a category-defining company.

Sinha couldn’t have predicted in 2013 that organized cyber criminals would soon launch a wave of ransomware attacks, in which data is essentially kidnapped. This type of crime would become a global crisis. With businesses looking for products to help safeguard sensitive information, Rubrik provided organizations with the means to make data more resilient across SaaS, cloud and enterprise environments.

From the beginning, that part of Rubrik’s business grew quickly.

Not only did organizations’ need for cybersecurity generate business, but Nithrakashyap says many at Rubrik were proud to be able to help a number of hospitals, schools, government agencies and businesses trying to shield themselves from ransomware. One of the high points for the company’s cybersecurity efforts came on March 9, 2020, when officials from the city of Durham, North Carolina shared how the use of Rubrik’s security products had been instrumental in the city’s relatively rapid recovery from a potentially devastating ransomware attack.

“We’re all humans and we’re all looking for purpose and meaning. Our partnership with the City of Durham is a true testament of how our employees, who we refer to as Rubrikans, help to make a difference in the communities we live and serve,” Arvind said.

Fever Dreams, Baby Showers, and Accepting Reality

Sinha traded VC life for the fever dreams and night sweats of an operator, which he experienced after realizing he was more than 45 days past launch and hadn’t hired anyone at Rubrik. He became the startup’s recruiter, despite not having hired anyone before. Eventually, Sinha got the hang of it, but only after spending many lonely days in a coffee shop across from Google’s campus, cold calling potential hires.

Sinha and his team once found themselves hosting a baby shower as part of an effort to win over the wife of a talented engineer they desperately wanted to hire. They agonized over the details, and left nothing to chance.Sinha and his team made sure to serve Mexican food, the favorite cuisine of the engineer’s daughter. Sinha noted with pride that the engineer remains a valued employee.

“We had situations when we were starting out, no product, no revenues, nothing, that we had to convince people with well-established jobs to join us,” Sinha said. And many families didn’t have two incomes. If you’re asking the primary breadwinner to leave a good job with a high-paying salary to join a startup, it’s not an easy proposition.”

No doubt that Sinha stays hyper alert to opportunities, especially in growing spaces like AI.

“What’s happening now is that because of AI, companies are pulling data across the enterprise, from all their different systems, which is creating a sweeping new surface area for attacks,” Sinha said. “The data has to be fed, discovered and labeled, with teams understanding the content and risk. That’s where Rubrik comes in.”

But to hear Sinha tell it, he’ll likely continue to choose the roads less traveled. He said that during his six years working as a VC, he adopted a critical philosophy, one that called for him to weigh the quality of his own perceptions and decisions against his own personal scorecard. He continues to embrace the idea.

“I remember the day I joined a VC firm for the first time,” Sinha said. “I had this clear thinking in my head that from this point onward, I’m making decisions to make myself happy as opposed to my bosses or other people around me. That was a clear inflection point for me. And it wasn’t egotistical. If I’m going to make decisions, particularly when it involves venture capital — with the huge bets and the huge amounts of uncertainty — I want to win or lose by my own intuition, as opposed to trying to make other people happy. I concluded that for good or bad, I’m going to make decisions based on what I truly believe is the right thing to do.”

Learn more about the Fortune Cyber 60 and Lightspeed CISO Survey.

“Not Exactly This” — How Sanjay Beri Hatched Netskope

By Rusty Weston

He’s sixteen and raising cash for college, performing IT support for Microsoft in Toronto, Canada. His boss pushes him a help desk ticket and says, “Go to the President’s office and fix his problem.” He thinks, wow, I’d better not mess this up. But then he sees that the big boss merely miswired a cable. “I left that room, going, ‘I can do this,’” recalls Sanjay Beri, who would later make good on that vow.

Viewed through the kaleidoscope of time, Sanjay’s trajectory to leading a tech company with a $7.5 billion valuation reflects a modest-means-to-riches inevitability. But the “fixes” he would undertake years later would never be that simple again. In 2012, Sanjay founded Netskope, growing it into an uncommon Silicon Valley success story. But success didn’t happen overnight, and there would be no linear progression to the top. Sanjay’s not a household name, but he’s gaining industry recognition because of his visionary actions, exceptional timing, hard, collaborative work, and guts.

Wait, how did this happen?

1. Sanjay didn’t expect it to be easy.

Sanjay continued at Microsoft. He worked on a team that created the first version of Internet Explorer and then helped create Office 95 right after graduating with a Computer Engineering degree from the University of Waterloo, outside of Toronto.

Along the way, he gained personal insight into the corporate need for cybersecurity. One of his fellow programmers was feeding Doom code into Microsoft Excel, the best-selling and award-winning spreadsheet. “I was like, wait a minute,” he says. He added his name to the Internet Explorer About box as a test, thinking somebody would scrub it out. But when no one noticed, he thought, “We’ve got some problems in this industry — this stuff can make its way through. And so, very early on, I got my taste of IT and security and some of the issues, and that was the beginning.”

A fellow Canadian computer science student named Arif Janmohamed, now a Partner at Lightspeed Ventures, met Sanjay in 1994. “He was arguably one of the top three people in the Waterloo class,” recalls Arif. “He’s obviously extremely sharp, extremely hardworking, very driven.”

In the intervening decade since they earned undergraduate degrees, Sanjay collected a Master of Science in Electrical Engineering from Stanford but then began to think twice about programming full-time. “I made my way to California in 2000, went to Stanford and did my Masters and realized I suck as an engineer. It took me a hell of a long time and a lot of money to realize that. You know, when you finish, usually you’re like, Wow, I graduated, I can do this. Sometimes, you also realize I want to do this, but not exactly this.”

Sanjay hadn’t unplugged his tech world cable — he’d fixed his career path. He doubled down on his Stanford degree with a UC Berkeley MBA. Sanjay also took his first foray into entrepreneurship, co-founding Ingrian Networks with one of his Stanford professors. There, he invented “DataSecure,” a product that encrypted transactions, which he eventually sold along with the company.

Then, instead of launching another startup, he became a tech exec, tackling progressively senior management roles at McAfee and Juniper Networks — where he became a VP and General Manager, building and leading a 300-person security product team.

Along the way, Arif became a VC and sought to nurture Sanjay’s talent, telling him, ”Look, you know, you can go the executive route, but you’re so talented,” says Arif. “You should go down the path of starting a company. A few years later, he called me up and said, ‘You know what, I’m ready.’”

Sanjay knew he was ready because he had, by his admission, “grounding in engineering, understanding of product platform — not being anywhere near the best at it — but understanding selling because I was out there selling from an early age.” Sanjay understood cybersecurity and said, “If you have a vision for it and the background in your domain, those are great ingredients to become an entrepreneur. I’ve always had the passion, the juice, and the intestinal fortitude to know that, hey, it’s not going to be easy. That’s what really set me up to start Netskope at that time in my life.” It was 2012.

2. Sure, in retrospect, the cloud seems obvious.

When Netskope started, the Software as a Service (SaaS) concept was far from dominant — least of all in cybersecurity, where clients, servers, perimeters and firewalls were all the rage.

Some people bet on this sea change. “You could see the green shoots of SaaS adoption, even in 2010 and 2012,” recalls Arif. “Only Salesforce was public at that point, but ServiceNow and Workday had already shown how enterprise applications should be built and consumed. And, that, to us, represented an opportunity for a new security paradigm to emerge.”

In retrospect, perhaps it didn’t take a genius to realize the business world would soon shift critical operations to the cloud. Yet it still took a genius or two to make that vision come true, spurring a transformation in how organizations protect their enterprise data and assets. Consider that in 2012, there weren’t many globally deployed, well-secured, cloud-based data centers. Zero Trust, which requires continuous authentication, wasn’t the crucible of anyone’s cybersecurity strategy. Digital transformations were yet to become all the rage.

Sanjay’s view of the cloud’s destiny was anything but cloudy. “I had foreseen leveraging the movement of data from your data center to the cloud. The reality is I felt we were at this inflection point in the world where the biggest market in security would transform, and I felt I’ve got to capitalize on this,” recalls Sanjay.

But first, he had to win over his family before approaching potential investors. “You have to know what you’re up for — you’re going to hit a lot of roadblocks — things aren’t going to go as planned. A lot of time, you’re alone trying to solve these problems. Your family has to be up for it, too. It’s not for the faint of heart, but you’ve never been for the faint of heart.”

Not surprisingly, the Beri clan proved to be the border pieces of the puzzle — the easiest converts. Next up were tech buyers — appealing to decision-makers Sanjay knew quite well. He’d led product teams at McAfee and Juniper Networks and met often with CISOs and CIOs. “At the beginning, you heard a lot of naysayers” about the cloud, remembers Sanjay,who estimated that “8 out of 10 CISOs” told him the vision was just plain crazy. “In many cases, that’s normal. If you’re trying to disrupt the market, (your vision) is not as apparent to others who might be investors, analysts, or your customers.”

Netskope offered the industry a big vision and, over time, would flesh it out. Sanjay describes Netskope’s vision succinctly as “How do I connect anything to anything and secure it and optimize it?” Netskope sought to converge network and data security in a method called SASE (Secure Access Service Edge) or, sometimes, the subset of SASE called Security Service Edge (SSE) that covers the “security side” capabilities. To realize that vision and to differentiate itself from its two largest competitors, Netskope has built “the world’s largest cloud network for security.” Netskope has earned Gartner’s coveted highest ratings for “vision and execution” in its 2023 SSE Magic Quadrant, according to CRN.

“I knew this cybersecurity market would never go away, and over time, it would grow bigger,” explains Sanjay. “Data would become a new kind of oil.” Then, in a widely chronicled megatrend, the pandemic accelerated business dependency on the cloud as an operating model. “It further validated that the way people work has changed,” adds Sanjay. “It built awareness of Netskope and what we do.”

3. Sanjay completes the puzzle.

There were two other essential puzzle parts for Sanjay to complete. First, attracting a world-class team, as every startup sets out to do. And second, luring backers who wouldn’t just write big checks but would find other ways to add substantial value. He knew these important pieces would fit together if he instilled a desirable corporate culture.

“It’s a competitive industry, but he’s managed to attract people who want to lean into building an iconic independent company,” says Arif, who serves on Netskope’s board and whose company has led or participated in numerous rounds of funding. He believes Sanjay attracts people who share his belief in a “team-first” culture. It’s where you can do your best work and lean into technical problems. This should be the last place you work.”

It’s not just about tech chops. Sanjay evaluates his team on factors such as collaboration and transparency — attributes you rarely hear about in Silicon Valley. “Those traits are important to us,” says Sanjay. “We metric people on those traits, and they’re rated on them.” His team is judged by how well they collaborate with others “no matter what the org chart says.” He emphasizes “self-awareness,” focusing on “what we need to do better. Not hiding that but actually making it a part of meetings, readouts, and all hands (meetings). That instills a culture of never getting complacent and getting better” in areas such as customer experience.

Sanjay didn’t reinvent the wheel when seeking funding for Netskope, but he applied his cultural compatibility litmus test. “For me, I pick my board members, my investors, the same way with my people,” Sanjay said in a recent video about his long-term relationship with Lightspeed Ventures. “Are they open, transparent, collaborative and innovative? And that’s Lightspeed. That’s who they are. That’s the number one reason I picked them.” It also didn’t hurt that he had a longstanding relationship with one of Lightspeed’s partners — trust is foundational to long-term relationships, not just ones involving funding and management.

Sanjay also believes that “Lightspeed has grown a lot during our journey. They’ve introduced growth and opportunity funds. They haven’t stayed stagnant — changing how they support entrepreneurs even when they’re public. With Lightspeed on my board, you want people who work well with other members. It sounds like a small thing, but having a well-functioning board is very important.”

Netskope has raised a sizable amount of venture capital in the past decade, roughly $1.5 billion, according to the company. Neither Arif nor Sanjay will commit to a timeframe for taking the company public, but Arif declares, “It is something that we will do.”

Sanjay’s Netskope story is far from over, but he’s presented a bold vision for cloud cybersecurity and executed it. Like nobody else.

Learn more about the Fortune Cyber 60 and Lightspeed CISO Survey.

Cato Networks Is Always Fortifying Your Security

By James Ledbetter

For decades beginning in the 1960s, there was a running gag in the Peter Sellers’ Pink Panther movie series. Sellers’ bumbling character Inspector Clouseau employed a man who was assigned to attack Clouseau when he least expected it, just to keep him on his toes.

That character’s name was Cato—the namesake for the Israeli-based cybersecurity and networking company, Cato Networks, recognized on this year’s Fortune Cyber 60 list, presented by Lightspeed.

Shlomo Kramer, Cato’s CEO, co-founded the company in 2015. But Cato is far from Kramer’s first stab at cybersecurity. His experience dates back to the earliest days of the public internet, when hacking was little understood but could immediately shut down a company’s computer system out of nowhere, a bit like Clouseau’s Cato.

Kramer, 57, recalls that the idea for his first company grew out of his youthful time serving in the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). The IDF regularly recruits Israel’s best math and science students as part of their compulsory military service, and placed Kramer in its elite 8200 unit, which focused on what was not yet widely called cybersecurity.

Kramer and his IDF colleague Gil Shwed took what they’d learned from their military service and founded Check Point, inventor of the commercial firewall and one of the earliest cybersecurity firms of the dot-com era. “We sat down and wrote a completely new type of product that fits on a single floppy disk, five minutes to install, and boom, you’re protected when you’re connected to the Internet,” Kramer recalls. “Today, it sounds trivial. But back then it was completely groundbreaking.”

Kramer looks at that early experience as a kind of 1.0 version of cybersecurity, that made him something of a celebrity within the cybersecurity world. Since then, he has founded another successful cybersecurity firm, Imperva, and now Cato Networks, a cybersecurity firm that is based in the cloud, where a huge portion of business takes place these days.

A recent Gartner report projects that by 2025, 80% of enterprises will have adopted a strategy to unify web, cloud services and private application access using a system like Cato’s, up from 20% in 2021.

“At the heart of what we do is complete obstruction of location,” says Kramer. And yet, for any Israeli company these days, location remains all too relevant. During a video interview for this article, one of the subjects stood up and started to leave the room because he thought he heard warning sirens. It was a false alarm, but a reminder that security threats are hardly a thing of the past.

The world of connected devices has expanded exponentially since Kramer and his colleagues first started thinking about cybersecurity. Even beyond the obvious increase in Internet-connected computers and smartphones, nearly every aspect of our lives is now hooked up to cyberspace: our cars, our refrigerators, our keychains. The size of the global cybersecurity market is currently about $175 billion and is projected to grow to $266 billion by 2027. “People work everywhere,” Kramer notes. “Applications are everywhere.”

Kramer saw early on that this was the trajectory for cybersecurity. As life became more digitized in the 21st century, the need for cybersecurity grew explosively, but in a clunky and fragmented way. The cybersecurity industry became dominated by global telecom incumbents, each peddling its own hardware-heavy and expensive solutions. For decades, networked computers in a given company or workplace were monitored by legacy hardware security approaches. Simply layering security on top of antiquated systems not only increased complexity but was often very costly.

“It became extremely hard to build a security solution that can meet the demands of digital business,” Kramer explains. “The agility, visibility, movement, and velocity — all of these things are extremely hard to do when you’re stuck in the previous generation with just a ton of appliances and widgets and whatnot.”

Kramer recalls attending a trade show in Paris in 2015 and viewing the presentations offered by the likes of AT&T and BT. After a couple of days, he called his partner Gur Shatz and said: “This is never going to happen.” The pair realized that a cloud-based cybersecurity solution was needed, and that’s how Cato was launched.

It’s not just that converging many network security tools meant fewer tools to learn and operate so security became simpler to run. Alone that would be revolutionary. But Kramer also understood that ironically with many security products came increased risk. Security teams understood less about their network as key data points were siloed behind the many different tools. Cracks in the infrastructure were left open between the tools, allowing threats to sneak through. With more tools, there were also more updates to apply.

As cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier once noted, a simpler network is a more secure network, and Kramer and Shatz understood that very well. So they converged those tools into the cloud where all sites, users, and cloud resources worldwide could be protected by the same global network security platform.

Cato’s signature innovation was recognized in a landmark 2019 Gartner report. Gartner coined the term “secure access service edge” (SASE), which Cato has since adopted as a kind of branding.

The timing was fortuitous. The outbreak of COVID in 2020 led to a massive shift among enterprises to hybrid work. The work-at-home phenomenon sent enterprises scrambling to evaluate, select, and deploy the necessary infrastructure to connect remote workers. For many, the process took weeks even months. But with Cato’s unique cloud-native architecture, enterprise customers were able to make the shift to hybrid work in hours.

Hybrid work was one powerful use case of Cato, but not the only one. Cloud migration

became much easier. Instead of purchasing premium cloud connectivity to connect cloud resources, Cato customers could easily connect cloud instances to the Cato SASE Cloud. Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) took a fraction of the time as enterprises found they could quickly connect and secure the new locations and remote workers with Cato.

Kramer likes to say Cato “brings Fortune 500 security to the masses” but no one should think that Cato is only being adopted by small companies or even specific industries. A look at Cato’s customer portfolio shows a diverse range of industries and company sizes.

For example, Carlsberg Group, the third-largest brewer in the world, selected Cato to transform its global infrastructure. “Cato is so much simpler to deploy and use than competing solutions,” says Tal Arad, Vice President of Global Security & Technology at Carlsberg. “We started referring to them as the Apple of networking.” When complete, the deployment will span 200+ locations and 25,000 remote users worldwide. Instead of the existing security appliances dotting their sites and locations, Carlsberg will rely on the full complement of Cato’s cloud-native security capabilities to secure and protect not only locations but also remote users worldwide.

“The savings we get with Cato and HoloLens are almost impossible to count,” says O-I Glass CIO CIO Rodney Masney at O-I Glass, one of the world’s largest glass bottle and jar manufacturers for leading food and beverage brands.

The Cato infrastructure was so much more efficient and effective than legacy approaches that O-I Glass engineers in the US could don Microsoft HoloLens augmented reality headset to show personnel in Asia how to troubleshoot factory problems. The company adopted Cato worldwide, improving security and user experience for its 24,000 work-at-home employees and 200 locations..

One way to think of SASE is that it combines the networking of computers with the idea of securing them. “We’re the AWS of network security,” Kramer says, referring to the Amazon Web Services, which provides compute and storage cloud services to more than a million businesses worldwide.

Still, even the most innovative businesses require funding and other assistance. Yoni Cheifetz has been an Israeli-based Lightspeed partner since 2006, and a tech entrepreneur whose path crossed with Kramer’s a few times over the decades. He recalls conducting a due diligence inspection with technical experts before Lightspeed invested in Cato in 2019. While he was impressed, he was also concerned that Cato was trying to take on numerous tasks at once. “I would probably not invest in something like this if it wasn’t Shlomo running it,” he says bluntly.

The Israel connection is crucial. Cheifetz and Kramer have known each other for years; Kramer is also an investor in addition to being an entrepreneur, and there have been board overlaps between Cato and Lightspeed for some time. “We are an Israeli company,” Kramer says. “All of the headquarters are in Israel. And we’re very proud of it. And that was a design goal for me.” Obviously, the country’s conflict puts tremendous strain on the company and its employees, but it’s also a fitting reminder of Kramer’s IDF roots.

While Cato has grown tremendously in its first few years of operating, the business nonetheless has its challenges. It’s well-known within the cybersecurity industry that finding talented employees is difficult. Some surveys have shown more than three million unfilled jobs in cybersecurity worldwide. “There’s simply not enough people out there,” Kramer laments.

Another complexity comes from artificial intelligence, which can multiply both the volume and complexity of security threats that any company or institution might face. Kramer approaches the issue philosophically. “The problem is not technology,” he says. “The problem is human nature. Once they invented the toothpick, the first usage was as a weapon.” The only solution, he argues, is to fight AI fire with AI fire.

One particular area where Cato has deployed AI is in halting phishing and ransomware attacks. Traditionally, cybersecurity firms have used lists of disreputable domains in order to identify potentially malicious emails. The problem is that the attackers can quickly generate new domain names that don’t appear on the lists. Cato now uses AI and deep learning to identify malicious domains in real time. In testing, its approach has identified six times more malicious domains than the reputation lists alone. “We are the first company to put AI into protection, not only detection,” Kramer says.

As advanced as the business may get, it’s always on the lookout for an attack on Clouseau.

Learn more about the Fortune Cyber 60 and Lightspeed CISO Survey.

How Arctic Wolf Became Leader Of The Pack

By Dan Tynan

Arctic Wolf is now a global leader in mitigating cyber threats for organizations of all sizes – from large enterprises to small businesses, one of a handful of companies driving the Managed Detection and Response (MDR) market. But when the company first launched in 2012, it was more of a lone wolf.

Back then, companies protected their networks and corporate assets via a jumble of complex point solutions: firewalls, anti-malware, intrusion protection, spam filters, email security gateways, network access control systems, VPNs, and so on.

Co-founder Brian NeSmith’s vision for the company – a web service that would aggregate and analyze the data from each of those point solutions, creating a “neighborhood watch for your IT infrastructure” – was so novel the category didn’t even have a name yet.

By the time the category became known as MDR, Arctic Wolf was already well established as a solution for small and mid-market businesses that couldn’t afford to field their own security operation centers.

As CEO, NeSmith himself made thousands of cold calls and wrote the scripts for other sales reps to use. At one point he even adopted an alter ego (“Brian Robinson”), because he feared that getting a sales call from the CEO would send the wrong message to potential customers.

As NeSmith told an interviewer earlier this year, he always started with a five-second script. If the customer didn’t hang up, he’d go for 15 seconds. If they were still on the line, he’d extend to 60 seconds. If they were listening after a minute, he’d ask for a 15-minute meeting. And if they were still on the fence after the meeting, he’d offer a free, one-month, no-obligation trial.

For the first five years of its existence, Arctic Wolf’s growth was steady but unspectacular. The company had yet to gain much traction among large enterprises, most of which continued to maintain their own security operations on premise.

Then the ransomware crisis hit the healthcare industry. Suddenly hackers were more than just a nuisance – they could make an organization’s data infrastructure inaccessible, costing them millions in down time. Almost overnight, NeSmith began getting invited to a lot more meetings with much larger companies.

Between 2016 and 2020, Arctic Wolf’s revenues soared by more than 4,300 percent. For the last four years, the company has been included in Deloitte’s Technology Fast 500. In 2021, it was declared an MDR MarketScape Leader by IDC and added to CRN’s Security 100 list. The next year it was included in CNBC’s Disruptor 50 List, an award it won again in 2022. This year the company was recognized as one of the top 100 private cloud companies by Forbes.

Today, Arctic Wolf is recognized as a global leader in MDR and XDR (extended detection and response), with more than a million licensed users worldwide. In addition to its global HQ in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, the company boasts regional offices in four states and eight countries.

“Our mission as a company is to end cyber risk,” says President and CEO Nick Schneider, who took the reins from NeSmith in August 2021. “By reducing the frequency and impact of incidents, we make our customers less attractive targets, bringing the risk to their environments to essentially zero.”

But without an early investment (and continuing support) from Lightspeed, Arctic Wolf might not be in a position to help anyone.

Lightspeed steps in

In 2012, NeSmith had a revelation: The security market was broken. There were too many point solutions, and no easy way to coordinate between them to identify the root causes of attacks. Along with co-founders Kim Tremblay, Sam McLane, and Matthew Thurston, NeSmith built a platform that collected data from all of these solutions and allowed security personnel to quickly analyze the results. They planned to sell continuous threat monitoring as a subscription service.

The founders had a vision and were building a team. Now they needed funding. So NeSmith turned to Lightspeed, which led a $7.2 million Series A round for Arctic Wolf with Redpoint Ventures. Seven months later, Lightspeed and Redpoint led the company’s $20 million Series B.

In 2018 the company secured an additional $16 million round from Lightspeed, Sonae Investment Management (now Bright Pixel Capital), Redpoint, and Knollwood Investment Advisory. All told, Arctic Wolf has secured six rounds of funding totaling more than $500 million, nearly all of it over the last five years.

As Arctic Wolf grew, Lightspeed continued to invest – a situation that’s relatively uncommon, notes Will Kohler, who heads up Lightspeed’s growth team.

“Not many investment firms have a strategy that enables them to invest in a company’s earliest stages and also be a real capital provider through every stage of its journey,” he says. “And few companies get the opportunity to go on that journey.”

What sets Arctic Wolf apart is its exceptional management team, well-organized go-to-market machine, and multiple opportunities to build relationships with customers via an expanding range of product offerings, he adds.

“Very few companies can execute on the vision of starting with an SMB offering and work their way up, customer segment by customer segment, to become a global service provider,” Kohler says. “Arctic Wolf is one of the rare ones that has.”

Acquire and conquer

Kohler says Lightspeed continues to have a presence on the company’s board and is involved with operational decisions, such as helping the company identify and recruit executive talent, as well as advising on the best paths for future growth.

“As a consistent investor in the cybersecurity space, we can help them understand what we’re seeing on the ground floor of the market,” he adds. “For example, we can identify adjacent areas they should look into, places where they might want to go deeper, and what product categories they may want to own themselves.”

And while Arctic Wolf has never subscribed to the ‘growth at all costs’ philosophy, says Schneider, it has been actively expanding its market footprint via strategic acquisitions. Over the last three years it has acquired RANK Software (analytics and threat hunting), Habitu8 (cybersecurity training), and Tetra Defense (incident response.

Most recently, the company announced its intent to acquire Revelstoke, makers of a leading Security Orchestration, Automation, and Response (SOAR) platform, which should enable better integration of data between disparate systems.

“We’ve always been thoughtful about how to structure and fund the business to maximize its long-term position,” he says. “We’ve spent a lot of time talking with Lightspeed about the investments we want to make, and we’ve been able to strike a pretty good balance between growth and stability.”

From the company’s earliest days, Schneider adds, Lightspeed has been a trusted partner and advisor.

“We’ve gone through quite a few fundraising rounds, market changes, and socioeconomic events over the last 11 years,” he says. “Through it all, Lightspeed has been extremely helpful in offering resources and expertise. It’s never felt like anything other than a true partnership.”

Learn more about the Fortune Cyber 60 and Lightspeed CISO Survey.

How 1Password Unlocked A New Market

By Reid Mitenbuler

When Jeff Shiner became the CEO of 1Password in 2012, one of his goals was to double the company’s size, from 20 employees to 40. Once that was achieved, he set out to double it again. Then again. And so on. By 2023, the company, which provides password management and other online security services, employed over 1,000 people.

During this time, the only thing that grew faster was the need for the Toronto-based company’s products. In recent years, incidents of global cyberattacks have increased anywhere between 38 and 57 percent year-on-year, according to various estimates; the one consistency is that, on a graph, they have the upward trajectory of a rocket. As AI tools become more sophisticated, cybercriminals become savvier, and digital technology entrenches itself even more in our work and home lives, cybercrime will likely grow.

So it’s no wonder that investors would be eager to get involved in the cybersecurity space, especially with companies like 1Password, which has earned one of the top reputations in the industry. For much of its existence, though—and to investors’ dismay—1Password hasn’t really needed outside help. Since the company’s founding in 2005, it has been profitable—and thus free to do things however it wanted, at its own pace.

Then, in 2019, 1Password decided to accept outside money. What, exactly, caused this shift in thinking?

“It became clear that we were missing real opportunities,” according to Shiner. This came as 1Password was in increasing competition to attract world-class talent in marketing, finance, and other areas. Because of the company’s historical self-sufficiency, it was a bit of a black box to outsiders who “knew almost nothing about us,” he said. “We were such a private company that people did not know whether we were successful, whether we were growing.” The funding helped them get experienced advice from investors while showcasing themselves to the world.

In 2022, 1Password brought in an additional $620 million—the largest venture financing in Canadian history, bringing the company to a valuation of $6.8 billion. In addition to Lightspeed, a number of prominent executives such as LinkedIn chairman Jeff Weiner, General Motors CEO Mary Barra, Crowdstrike CEO George Kurtz, and Walt Disney Company CEO Robert Iger as well as celebrities such as Ryan Reynolds, Matthew McConaughey, and Trevor Noah invested in the company. These individuals not only recognized 1Password’s value, but could also help the under-the-radar company market itself. “Everybody knows who these sorts of folks are, and everybody will pay attention,” Shiner said.

According to Shiner, “a big reason why we brought on Lightspeed” was because it offered 1Password yet another opportunity to leverage the valuable knowledge and connections of people who have tread some of the paths 1Password is about to tread. There’s almost no issue someone at Lightspeed hasn’t dealt with that could come in handy to Shiner when making a big decision or dealing with a tricky situation.

Long before 1Password started raising funding, Lightspeed had been eyeing the company. “I’ve been using 1Password personally for a long time,” Anoushka Vaswani, a partner at Lightspeed, said. Not only did she like how easy the product was to use, but she was also impressed by the kind of “forward-thinking” organizations that also used it, such as Gitlab, IBM, Slack, and Under Armour.

Vaswani was also impressed by 1Password’s possession of the kind of “incredible business fundamentals that you just don’t see a lot,” she said. When Lightspeed first met Shiner, 1Password was “well over $100 million in ARR”—annual recurring revenue. She was also impressed that the company had achieved its level of scale without the sort of sales effort which most other companies would need to reach that level.

Regarding 1Password’s growth, Shiner had started registering a fundamental shift in the company’s sales around 2013—one that the company has pivoted to over time. Previously, most of the company’s sales were consumer focused. Then, around the holidays, Shiner noticed that businesses were starting to buy 1Password as a gift for employees. Not only was this a thoughtful thing to do to keep employees safe at home, but it also served the employers’ interest. As technology continued integrating itself into people’s professional and private lives, the links between those two spheres also grew—increasing the risk that a security lapse in one area would spread to the other. Despite their frequent portrayal in movies and television, devastating data breaches aren’t often the result of sophisticated, network-level hacks; they’re often the result of sloppy personal habits, such as using the same password—or guessable passwords—for all of one’s accounts.

Once Shiner saw the demand from companies—he realized the importance of building the company’s business-to-business arm. Companies saw 1Password as a crucial solution in combating their primary reason for data breaches: weak, reused credentials. This revelation was a result of “listening to our customers but also listening to where the value is, so that you’re not just building an innovation and an idea, but you’re building an actual product, where you understand what part of that customers find valuable and are willing to pay for,” he explained.

Today, 1Password has increased its focus on building its B2B business, roughly two-thirds of the company’s ARR comes from that revenue stream, according to Shiner. This fundamental business shift presents the company with a new challenge: informing potential customers just how much the company has changed. “People first encountered us as a consumer password manager more than as a B2B security leader r, even though we’ve got well over a hundred thousand businesses who rely on us every day,” he said.

Going forward, as people’s personal and professional lives increasingly intermingle on digital devices, especially with the rise of hybrid and remote work, and as cybercriminals become ever more capable, Shiner and Vaswani both expect 1Password’s products to become more valuable. Both have witnessed AI’s potential to create phishing attempts that are so realistic and highly specific to the target that they make past phishing attempts seem primitive in comparison. “I think AI just really increases the threat vector,” Vaswani said. “It really increases the need for a solution that can protect credentials across an organization, regardless of what tool you’re using.”

It’s hard to know if AI presents more threats or opportunities to the cybersecurity space. In any case, it’s already having ripple effects that 1Password is poised to address. “One of the things I’m starting to hear now is that companies are struggling to get more cybersecurity insurance,” Shiner said. “It reminds me of what’s happening with natural disaster insurance in Florida—it’s just too costly for the insurance companies. It’s an indication of the increase in risk.” As cybercrime becomes more sophisticated and companies expand the number and complexity of applications employees can access from anywhere, closing the loops across an organization’s security infrastructure becomes even more important.

Shiner has to consider some of the worst things that can happen in the world—cybercrime, natural disasters, ransomware, etc.—in order to prepare to defend against it all. But in person, he’s incredibly upbeat and optimistic. Perhaps that’s because 1Password products offers something that, at its core, is invaluable in this day and age: peace of mind.

Learn more about the Fortune Cyber 60 and Lightspeed CISO Survey.