04/15/2021

Enterprise

The Developer Productivity Manifesto Part 2 — More (Developers) Isn’t Always More

In software development, more (developers) isn’t always more.

In part 1 of “The Developer Productivity Manifesto,” I argued that developer productivity, measured in terms of new software, falls over time as low-hanging fruit is picked and new ideas become harder to find.

An understandable response would be — why not just throw more engineers at the problem?

If you’ve ever worked in software development, you know adding more cooks to the kitchen rarely helps. For those who haven’t worked in software development, this essay tells you why.

The Developer Productivity Manifesto has three parts, this is part 2:

- Part 1: The Developer Productivity Flywheel

- Part 2: More (Developers) Isn’t Always More (you are here)

- Part 3: Leaving Software on the Table

The Mythical Man-Month

“The Mythical Man-Month” is a classic and hugely influential book about software engineering and project management. Across a series of essays, Fred Brooks (himself a former IBM project manager) lays out the cognitive errors software development teams tend to make in estimating the time to completion for software projects. His core thesis is best encapsulated by Brooks’ law.

Brooks’ law of software project management states that:

Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later

If anything, adding more cooks to the kitchen lengthens cooking time. We shouldn’t assume a simple, linear, and directly causal relationship between developers as inputs and software as output. He lays this out in dire terms:

… when schedule slippage is recognized, the natural (and traditional) response is to add manpower. Like dousing a fire with gasoline, this makes matters worse, much worse. More fire requires more gasoline, and thus begins a regenerative cycle which ends in disaster.

This counterintuitive phenomenon has multiple causes:

- Ramp up time: Even seasoned developers take time to get up to speed on new projects, and newbie engineers must learn core skills on top of company-specific ones

- Communication and coordination complexity: The larger the team, the harder it is to coordinate productive work and communicate progress across teammates

- Indivisibility of work: The basic unit of work in software development can’t always be divided among multiple contributors

That last point forms the basis of the title and main thrust of the book, the fallacy of “man-months” — distinct units of work achievable by a single developer in a set period of time. As Brooks argues, there is no such thing, and thus we should be wary of simplistic solutions to complex endeavors like software development.

Software is not labor-intensive. Not many people are necessary in order to produce good software… What makes or breaks a project, it’s the amount of FOCUS developers can pour into it — RedBeardLab

Diseconomies of scale

While it is common to assume economies of scale, diseconomies of scale are arguably just as relevant in software development.

Diseconomies of scale are where unit costs (the costs of producing an additional unit of output) increase rather than decrease with scale. Here, it’s better to cut back or lower output, rather than maximize it. Despite many advances, these occur more often than we’d like to admit in modern software development.

Diseconomies of scale can take many forms, and many overlap with the underlying causes behind the mythical “man-month”:

- Complexity: Things become disproportionately complex as they scale, as complexity increases non-linearly with size. Complexity creates overhead, making large organizations less efficient than medium-sized ones. Bureaucracy is one manifestation, but there are others.

- Black Swans: Large systems fail in spectacular fashion. It’s why big companies create systemic risk while small businesses and startups fail in the thousands without cause for alarm. Within software, this might be a large monolithic application, prone to serious, single point failures.

Humans, being the independent and unpredictable automatons we are, are especially prone to diseconomies of scale. Coordination costs eventually overwhelm even the most thoughtful engineering leaders. Application deployments are themselves quite brittle, necessitating vastly more manpower and attention as they grow.

We will never have enough software developers

Senior executives report that the lack of developer talent is one of the biggest potential threats to their businesses — The Developer Coefficient 2018, Stripe

Executives believe that insufficient developer talent is one of the biggest threats to their business, and yet there’s good reason to think this might never be solved.

As I discuss in a previous essay, Why We Will Never Have Enough Software Developers, changes in the underlying technologies of modern software development whittle away the accumulated human capital of software developers:

Specific skills in software development quickly become dated. Programming languages and development frameworks go out of style. Hadoop is hot one year, and it’s old news the next. Like a fast, expensive car that quickly loses value as it’s driven around town, the skills and human capital of software engineers fall apart without constant, expensive maintenance

Though young engineers can keep up with the latest programming languages, frameworks, and tooling, eventually the torrential wave of new tools becomes too much to bear, and developers either tune out or drop out:

At age 26, 59% of engineering and computer science grads work in occupations related to their field of study. By age 50, only 41% work in the same domain, meaning a full ~30% drop out of the field by mid-career

The never-ending drumbeat of new technologies drives developers out of the field. New tooling is important and valuable, but their overall effect on developer productivity depends on how much they upend existing workflows and place additional burden on already taxed developers.

As I conclude:

Growing the supply of software developers is not trivial because the field already sees high levels of developer dropout and turnover, and this would only increase if the field were to grow larger.

I favor efforts to grow the software engineering talent pool, but if we’re not careful, like quicksand, our efforts will be counterproductive.

More developers, lower productivity

As we saw in part 1, more researchers don’t necessarily lead to faster progress. In the case of Moore’s Law, it merely maintains the rate of progress, at significant expense.

But is this true of the economy overall? It turns out, the answer is yes. Cross-industry data proves that simply throwing more people at a problem doesn’t work.

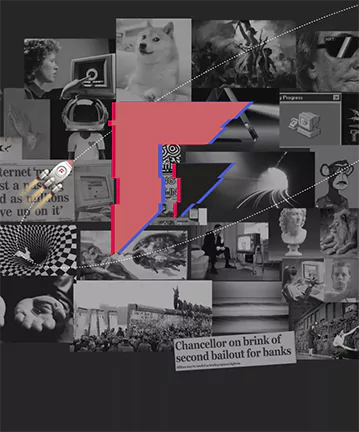

The chart below plots the growth in the number of employed researchers and their productivity levels (measured in terms of revenue growth generated per researcher) for ~1,700 publicly-traded U.S.-based companies over a 20-year period. Most firms “threw more bodies at the problem” (orange histogram > 1), but ~80% of firms saw declining research productivity (blue histogram < 1):

Hiring more researchers doesn’t necessarily cause productivity to decline, but regardless, growing research teams and declining productivity go hand-in-hand more often than not.

Software development could fall prey to the same trap. Most companies are growing the number of software engineers they employ, mirroring the researcher employment trends, but let’s not forget productivity:

Research productivity, and analogously developer productivity, falls over time unless acted upon by an outside force. Like gravity, this phenomenon is pervasive and ubiquitous, a force field dragging down all idea-generative industries.

Busy work doesn’t work

I love this quote from Stripe:

Despite the number of developers increasing year-over-year at most companies, developers working on the right things can accelerate a company’s move into new markets or product areas and help companies differentiate themselves at disproportionate rates. This underscores the most important point about developers as force-multipliers: It’s not just how many devs companies have; it’s also how they’re being leveraged — The Developer Coefficient 2018, Stripe

In my last essay I talked about the importance of measuring productivity in terms of new software output. Another reason why more engineers is not necessarily the solution is that much of the value of the marginal engineer is in their innovation activities rather than their maintenance work.

We can quantify the impact of engineering time spent maintaining old code rather than writing new code. According to one analysis, an engineer engaged in purely non-innovative activity destroys nearly $600K in employer market value. On the other hand, the average engineer, working on a combination of maintenance and innovation activities, adds $855K in market value to their employer.

As the study’s author speculates:

… the value of the engineer is a bundled combination of maintenance activities which have negative value and innovation activities with positive value

Further, he echoes Brook’s Law:

It may also be the case that more engineers does not always make for easier problem solving and on the margin, removing innovative activity, [they are] a net drain on the firm’s value

I want to be clear: maintenance matters too. When things break, as they inevitably do, development teams must stand at the ready to fix problems and bring systems back online. This is critical work that should not be minimized in a narrow pursuit of newer, shinier objects.

That said, mere maintenance is table stakes. It doesn’t pay the bills — an engineer’s salary, first and foremost.

Hidden figures

Again, Stripe gets it right:

While many people posit that lack of developers is the primary problem, this study… found that businesses need to better leverage their existing software engineering talent if they want to move faster, build new products, and tap into new and emerging trends — The Developer Coefficient 2018, Stripe

Notice the emphasis on newness and speed. We can and should grow the talent pool for software engineering, but we can also do a much better job with the engineering talent we already have.

Maintenance matters but so does fundamental innovation. As software projects grow, and their teams with them, thoughtful engineering managers must strike the right balance or see their most precious resource go to waste.

Industry-wide we are, unfortunately, out of balance. In my next and final piece, I’ll explore exactly how much software we’re “leaving on the table” as a result.

Ready for more?

Follow me on Twitter, subscribe to my monthly essays here, and reach out to me directly via nnamdi@lsvp.com

Authors