Mostly Metrics’ CJ Gustafson interviews Lightspeed Partner Sebastian Duesterhoeft, the “Michael Jordan” of TAM

Total Addressable Market is something you can’t unsee once you see it. It changes the way you assess the world around you. To the chagrin of my wife, I can’t visit a bakery without doing the back-of-the-envelope TAM on blueberry muffin sales in the greater Boston area.

Having built a plethora (vocab word!) of TAM analyses as an operator when either evaluating a new product launch or building a pitch deck to ask VCs for money, I finally got the chance to approach the topic in detail from the lens of an investor.

From the very first Salesforce export we pored over together, Sebastian Duesterhoeft has been one of my favorite investors to work with and learn from.

After a remarkable stretch at Coatue, where he invested in category defining companies like Snowflake, Databricks, Confluent, Lacework, and Airtable, Sebastian recently began a new chapter as a Partner at Lightspeed Ventures, focused on growth-stage investments in enterprise software. The firm raised more than $7B in new capital over the past year, with $4.5B dedicated to investing in growth-stage companies.

So grab your popcorn, and enjoy this masterclass from the Michael Jordan of TAM.

Part I: Why is TAM important, and how do you calculate it?

Why is TAM important to investors? For all the founders out there working on pitch decks, how “large” is a big enough market, from your perspective, in dollar terms?

- The size of the TAM ultimately determines how much revenue a company can capture over time. A company can’t “outgrow” its TAM, but rather will end up capturing some fraction (market share) of the TAM.

- How “large” is big enough actually depends partially on the fund you are pitching. Venture fund returns typically follow a power law (e.g. 80% of the returns are generated by 20% of the investments). As a rule of thumb, investors will often want to see a scenario where any given company could theoretically return the fund 1x. So, if you are talking to an investor managing a $500M fund, the investor would be looking for a $500M return potential. The simple math then would be in order to generate $500M returns, at 20% ownership the company needs to be valued at $2.5B at exit. Assuming we are looking at a software company we could very simplistically assume a 10x exit revenue multiple (generous!) which would imply the company needs to reach $250M in revenue at exit. However, it’s important to realize that when the investor sells, there has to be another buyer that is actually willing to pay a 10x revenue multiple. For that to happen, the next investor (potentially a public market investor at IPO) still needs to see a meaningful growth opportunity. 15–20% required return for that next buyer would imply a 2x over 5–7 years, at which point the company would have to be $500M+ in revenue. Now, to bridge from the revenue needed to actual TAM, a simple framework could be that market-leading horizontal SaaS companies will get to ~20% market share over time (Salesforce.com has ~20–30% market share in core CRM today, vertical SaaS companies often get to higher market share). This implies a $2.5B TAM opportunity is required to give an investor with a $500M fund the opportunity to have a “fund-returner”. When you are talking to a later stage investor, where return expectations are often a bit more bounded (3–5x) the expectation may no longer be to have “fund-returners” but the manager of a $5B fund would still expect for an investment to be able to return at least 10% (i.e. $500M) to make the investment “worth the time”. It’s important to keep in mind who the audience is you are talking to. I’ve definitely struggled with having to tell founders that a $1B exit may not be big enough. By any standard, building a company to a $1B exit is an incredible accomplishment, yet for a large fund the absolute return dollars are often too small to move the needle enough.

What frameworks are out there for calculating TAM? Which approach is the best, in your opinion?

- At the core of any TAM is a P x Q (price x quantity) framework. I think it’s really critical to think hard about what the P x Q for your market is. The P in theory is relatively straight-forward; it’s the price a company sets for its product. In reality it’s a bit more complicated because a) setting a TAM maximizing price isn’t an easy exercise, and b) P might change over time as competition increases. That said, the Q is typically what is much more difficult to determine. It’s relatively easy if your product is priced on a per seat basis, e.g. a DevOps product going after the # of professional developers (~13M in the US + Europe). It gets a lot harder for a product like Snowflake which is priced on a somewhat difficult to grasp volumetric basis depending on the amount of compute and storage used by a company. A workaround in those cases can be to try to determine what the spend potential of “typical” SMB/mid-market/enterprise customers is, which then allows you to extrapolate that spend to the # of companies out there in each of these size buckets.

- I am also generally a fan of trying to come up with very simple reference checks. For example, it’s pretty well understood that companies tend to spend ~7–10% of their infrastructure cost on security products securing that same infrastructure. When cloud security (e.g. Wiz, Lacework, Orca) started to really emerge as a big trend in 2019/20, many investors (including myself) got excited by the trend based on the very simple belief that over time, companies would spend at least 3–5% of total cloud infrastructure spend on cloud security. When you consider the amount of total cloud spend today just between the three large hyperscalers (AWS + Azure + GCP are ~ $150B in revenue in CY’22), even a small “take rate” on that market is huge. These simple frameworks can be particularly helpful when you are looking at a new market.

- A big red flag for me is when founders simply use TAM numbers from Gartner/IDC in their pitch decks. More often than not, founders don’t even know really what is included / excluded from those numbers and how the research firms came up with the estimates. Just using Gartner/IDC numbers likely means that you don’t have a good sense yet for who you are selling to (the Q) and how you should be pricing your product (the P).

I hear derivative terms like SAM — Serviceable Addressable Market, and SOM — Serviceable Obtainable Market thrown around? Are these terms important? Do you calculate these as well when looking to invest in a company?

- I do believe it’s important to think about what part of a market is really serviceable for a company — today and in the future. A few things to consider that can limit the serviceable TAM:

- What part of the market can the company acquire economically, e.g. are there some customers that are just too small for a company to acquire with the required GTM model?

- Is there a part of the market that a company’s product can’t address well, e.g. very large customers might have requirements the products can’t meet today (and potentially in the future)

- For an existing market with incumbent vendors, how quickly can the market realistically “roll-over”? In many cases it’s unrealistic to think that companies using incumbent solutions will just decide to shift to the new vendor. Existing (lengthy) contracts or significant transition cost can create friction that reduces what % of the market will turn-over to the new entrant every year. I find this to be particularly important for vertical software markets with existing (often on-prem) incumbents that are deeply integrated into their customers’ operations. Even for a much better (cloud-based) product it will take time for customers to make the transition.

Part II: Using TAM for investment decisions

During the COVID years we saw some, to put it nicely, “super premium” valuations in both public and private markets. Can you think of any examples where the valuation just didn’t make sense, specifically because of TAM?

- I think one of the biggest mistakes people (including myself) made in 2020/21 wasn’t that we paid big prices, but that we paid really big prices for almost everything, with little regard for the TAM opportunity and the competitive setup in a space. Specifically with regards to TAM, a couple of good examples where we got things really wrong in my view are vertical SaaS and the modern data stack.

- Vertical SaaS companies historically always traded on lower revenue multiples(don’t yell at me for using revenue multiples as a shortcut!) vs. horizontal players. One of the drivers is the idea that vertical SaaS companies tend to grow more linearly into a more constrained TAM vs. horizontal players. Even though there are undoubtedly some very large vertical markets, I still think the prior statement generally holds true. During 2020/21, the gap between vertical and horizontal players basically disappeared and there were vertical players that raised capital at 100x ARR and public companies that traded at 20x forward revenue. Post IPO, nCino traded at >40x forward revenue — a premium to Datadog at the time!

- The example of the modern data stack is a bit different and arguably hasn’t fully played out yet, but in my view also represents a failure in thinking deeply enough about TAM. Once the success of Snowflake became obvious, investors became so enamored by the trend that quickly 3–4 vendors in each of ETL, reverse ETL, data cataloging and data monitoring raised at sky-high valuations. My best estimate is that when a company spends $100 on Snowflake, that same company is likely spending no more than ~$20–25 on ALL other parts of the modern data stack combined. While Snowflake is a ~$40B market cap company today, I believe some of the other parts of the modern data stack will struggle to give rise to $5B+ market cap companies. I suspect the same mistake is being made all over again with the AI/LLM stack right now. We (investors) get so enamored with the narrative of a trend that we keep placing bets on smaller and smaller parts of the stack.

How do you assess the market opportunity for vertical SaaS? I’ve heard that investors sometimes shy away from these types of companies because they think the market opportunity is too small… Is that true? If so, are there any outliers?

- This is a topic I am personally a little bit torn on. Intellectually I am really intrigued by vertical software companies because of a number of characteristics outside of TAM that can make vertical markets really attractive. The vertical focus often allows them to become much deeper integrated into the value chain of a vertical, capturing a lot of value along the way and becoming incredibly sticky. The leaders in a vertical also end up capturing much higher market share than leaders in horizontal markets, and over time this can lead to really high terminal margins (often higher than in horizontal markets).

- All that said, TAM still often ends up being an issue. There are definitely very meaty, large TAMs such as Veeva in healthcare, Procore in construction, or Toastin restaurants. However, Veeva, the vertical CRM, is still $25B vs. $175B for Salesforce, the horizontal CRM (hugely simplified, Salesforce is obviously much more than just a CRM today but I think the argument still stands — CRM Sales Cloud revenue is ~3x Veeva’s total revenue).

- There simply aren’t a lot of examples of $10B+ outcomes in vertical software (by my count ~5–6 today) and for very large funds that require $10B+ outcomes (as discussed under 1) that just makes it harder to bet on vertical SaaS.

Part III: Growing TAM

Is there such a thing as “being in the right TAM at the right time?” Does TAM have a maturity, or time, aspect to it?

- Absolutely. I like to think about TAM maturity as S-Curves. You don’t want to be too early, when the market is still in the very early, flat part of the S-Curve where it takes a long time for value to be captured. Ideally you want to “catch” a market when there is a clear catalyst that drives the transition from the flat part of the S-Curve to the steep part of the S-Curve.

- Looking at the example of cloud security again, the key underlying catalyst was when for a broad set of companies the center of gravity for their infrastructure moved from on-prem to the cloud. The first generation of cloud security companies, e.g. Evident.io, Redlock (both ultimately acquired by Palo Alto Networks) were likely still a little bit too early, but by the time Wiz, Lacework, and Orca came around, the need for cloud security was very evident.

- Two counterexamples of markets that are likely past their prime are eSignature and video conferencing. Both Docusign and Zoom went through unprecedented growth through COVID, jumping forward on their respective S-Curves from the early steep parts to the late, flat parts.

How do you think about Expansion dollars when it comes to TAM? Do founders need to articulate where they’ll go after their initial product’s TAM?

- Extensibility is the key driver behind durable revenue growth. The initial TAM of a company will eventually run-out, or at least enter the later stages of the S-Curve where growth will become harder and harder to get by. At the earliest stages I am looking for a founder’s ability to articulate a strategy that will allow the company to expand the initial TAM. At the growth stage I’d like to see some actual proof points in the form of new product launches or new verticals that start to contribute some ARR. At the late stage the 2nd and 3rd products ideally start to contribute significantly to total ARR (~20%+ of total).

- The exact timing of when to go multi-product can vary a lot. A very deep initial TAM can afford you to wait a bit longer with product #2. Regardless, I believe that it’s valuable to start thinking about expansions early and make it part of the company’s DNA. Building this muscle later is going to be difficult. A good example of a company that had the “platform-DNA” from the very beginning is Gitlab.

Part IV: Companies nailing TAM

Which companies do you think have expanded their TAM most artfully?

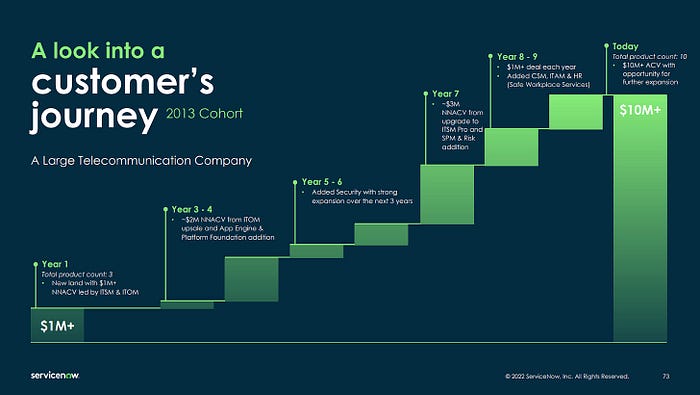

- In the public market, two of the best multi-product stories are Datadog and ServiceNow, in my view. If you look back at their analyst day presentations since their respective IPOs you’ll see them both adding a new “slice” of TAM effectively every year. At the time of the IPO, ServiceNow was going after a core IT TAM of ~$14B. A decade later, ServiceNow’s TAM is ~$175B and the company forecasts ~$16B in revenue by 2025, more than the entirety of its initial TAM. The results of ServiceNow’s success expanding their platform becomes clear when you look at the customer case study below:

- A few additional stats that are pretty mind blowing with regards to ServiceNow: The company has >1,300 customers paying them >$1M/year and >23 customers spending >$20M/year on ServiceNow.

2. Datadog is another awesome example of a company that has done an incredible job continuously expanding their product surface and as a result their TAM. The picture below tells the story:

3. In the private universe, Rippling is doing an incredible job expanding beyond core HRIS. I find Parker Conrad’s notion of a “compound startup” to be very compelling.

- Rippling has very rapidly gone beyond “just” the HRIS. If they continue to execute, Rippling stands a chance to own a lot of the back-office functions within small and medium-sized businesses (with Hubspot potentially owning the front-office).

Part V: Lightning Round

If you could put one message on a billboard for startup founders to drive by and read every day, what would it be?

- “Do you really get an ROI on this billboard?” Just kidding…but in all honesty, I’ve just always struggled to see if these billboards are actually worth it or more of an ego thing. But admittedly, I’ve never actually done to work to figure it out.

What’s changed the most in terms of how you think about “what makes a good investment” since you started your career?

- I find it to be a constant learning process

- I started my career more in the private equity world and with probably too much of a belief that all the answers are in the numbers. With time you realize that the numbers are only the ultimate expression of business qualities that are developed way before they show up in the numbers.

- 2022 and the first few months of 2023 for me have really been about refocusing on a lot of the basics of what makes good companies. I actually sat down in Q4 of last year and spent a lot of time just writing down how I think about what makes a good company (e.g. durable growth — TAM, TAM maturity, extensibility, growth forecasting — and terminal margins — terminal margin structure and defensibility of margins).

This article republished with permission from Mostly Metrics.